Spirituality

What did these saints do, in their tombs, for the time between Friday afternoon and dawn Sunday?

Pakaluk

According to St. Matthew, at the moment Jesus died, the curtain of the temple was rent from top to bottom (and therefore not by human hand). Also, the earth quaked, and "the rocks were split" (27:51). He uses the same verb for the splitting of the curtain and the splitting of the rocks, as if one and the same force was responsible for each.

The phrase "splitting of the rocks" is odd, as if the reader should understand which rocks were split. Why not just "rocks" or "some rocks," but rather "the rocks?" Early Christian tradition takes them to be the very rocks of Golgotha. Indeed today, in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, one can see "the fissure in the rock," which starts at the base of the Cross of Golgotha and extends all the way down to "Adam's Chapel" below Golgotha.

Matthew says that the centurion and those around him "saw the earthquake and the things that took place." Presumably, the things that took place included the splitting of the rocks. If, during an earthquake, the very rocks on which they were standing split apart -- no wonder that they were "filled with awe," as Matthew says (v. 54). And therefore, he calls them "the rocks," using the plural, because after they split, of course, they are two.

So this expression, "the rocks were split," is the way an eyewitness might speak, or someone who was used to pointing out the place of the crucifixion and the evidence left there of the earthquake.

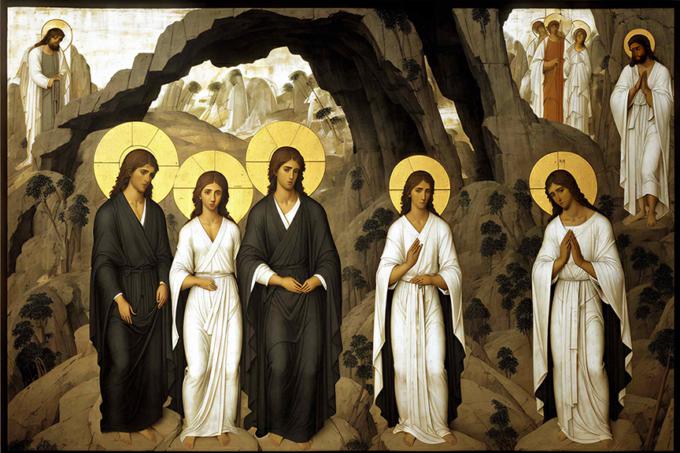

For me, the most interesting sentence of Matthew's description is this: "The tombs also were opened, and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised, and coming out of the tombs after his resurrection they went into the holy city and appeared to many," (vv. 52-53).

Almost every word is interesting. Note that the tombs were simply "opened," a softer term, rather than split open, as if suggesting it is not by force but by some kind of invitation that the dead will rise.

And then Matthew says that "the bodies of the saints" were raised, not simply "the saints," which shows clearly that he identifies "the saints" with their souls already in heaven, so that what is in the tombs is not them but only their bodies.

And then he calls them "the saints." Actually, in Greek, it is a masculine term, and so, strictly: "holy men," but presumably it means "holy men and women." However, this is interesting because then Matthew is comfortable speaking about sanctity and saints prior to the founding of the Church. Were these "saints," perhaps, disciples of Our Lord, already baptized by the Apostles, who, like Lazarus, had died during the three years of Our Lord's public ministry? Or were they from earlier generations, like Zechariah and Elizabeth?

Notice the expression, "fallen asleep," which is how Jesus taught the disciples to speak about death, when he spoke about his friend Lazarus. Remember the Gospel of John? -- "Our friend Lazarus has fallen asleep, but I go to awake him out of sleep" (11:11).

And then there seems to be a delay between the opening of the tombs, and the bodies being raised, and their coming out of the tombs. Something you cannot easily see in translation, but you would need to read in the Greek, is this. In Greek, the term for "bodies" is neuter. But when Matthew writes "coming out of the tombs ... they went into the holy city," he uses the masculine, which picks up "saints." That is to say, although the bodies of the saints were raised, the saints went out of the tombs and into the city.

Here we have implicit testimony to that important article of faith, "I believe in the resurrection of the body." Although the soul of a saint who is "asleep" is in heaven, the soul is not restored in its integrity until it is joined with its body.

What did these saints do, in their tombs, for the time between Friday afternoon and dawn Sunday? It was some kind of vigil and fast -- no doubt the earliest observance of that holy time in Christianity, since these saints observed the time as believers, whereas the Apostles had fled in fear and were hiding. (But these saints were spiritually united with Mary, who would have been keeping the vigil also.)

The Fathers like Matthew's expression "the holy city." Indeed, today one of the best reasons for a pilgrimage to Jerusalem is that it remains "the holy city." The Fathers say that it could receive this special designation because no idols were worshiped there; but also, because the Lamb had just been sacrificed there.

The saints delay entering the city until Jesus had risen and gone there. If their tombs were right outside the city, like the tomb of Jesus, they might have been seen anyway. Perhaps the open tombs were frightful and provided a reason why no one, apparently, went to the garden before the resurrection.

But what happened after the resurrection? Did these saints die again, like Lazarus? The Fathers are split on the question, but St. Thomas Aquinas finds the better opinion to be that to die again would be an unbearable suffering for them, and therefore they remained alive until the Ascension and then ascended in heaven with the Lord.

- Michael Pakaluk, an Aristotle scholar and Ordinarius of the Pontifical Academy of St. Thomas Aquinas, is a professor in the Busch School of Business at the Catholic University of America. He lives in Hyattsville, MD, with his wife Catherine, also a professor at the Busch School, and their eight children. His latest book is "Mary's Voice in the Gospel of John" available from Amazon.

Recent articles in the Spirituality section

-

Pushed off the platformMichael Pakaluk

-

Advice to fathersMichael Pakaluk

-

The higher you go liturgically, the lower you should go in service of the poorBishop Robert Barron

-

The Easter Season is the fleshly seasonMichael Pakaluk

-

Ripley and RupnikEffie Caldarola