Faith

Catholic worship never abandoned the use of Scripture in the liturgy, but the council found it important to re-emphasize the scriptural foundation of the liturgy.

SJ

We've been reviewing the central principles of Vatican II's Liturgy Constitution (Sacrosanctum Concilium). These principles have included liturgy as the principal manifestation of the church, Christ as the subject of the liturgy and full conscious and active participation.

Pursuant to these, the document defines the two-fold purpose of the liturgy as the glorification of God and the sanctification of the people. Hence, the liturgy is "the summit (glorification) toward which the activity of the Church is directed; it is also the fount (sanctification) from which all her power flows." (#10)

Perhaps because of the constitution's insistence on the centrality of the assembly's full, conscious, and active participation in the liturgy, the document's framers also found it necessary to insist on a balance between the role of the priest "who, in the person of Christ, presides over the assembly" (#33) and the vital importance of communal celebration of the liturgy. Thus, the liturgy is communal and hierarchical at the same time. By the same token, SC notes the importance of a variety of ministerial roles in the liturgy, above and beyond that of the priest. (SC 26-31) Precisely how priests and people are related in liturgical celebration remains an ongoing theological issue.

Another major theological feature of the constitution is the insistence on the importance of faith, conversion, and preaching. (SC 9, 24, 35) As St. Paul writes (Romans 10:17): "faith comes by hearing." Therefore, the liturgy is never an automatic act; it always involves faith and proclamation. Catholic worship never abandoned the use of Scripture in the liturgy, but the council found it important to re-emphasize the scriptural foundation of the liturgy. It can be fairly said that in light of the 16th-century Reformation debates, this renewed attention to the Bible was a significant ecumenical advance.

Pastoral Directives -- Principles of Revision

Sacrosanctum Concilium did not stop with basic principles but developed their pastoral consequences. The most obvious and perhaps significant practical liturgical reform to come out of the council was the decision to allow the use of the vernacular in the liturgy. Official permission had already been granted to translate certain parts of the sacramental rites, e.g., baptism, into the people's language, but the council mandated a more extensive endeavor.

However, the council fathers did not have a complete translation of the liturgy in mind. After stating that Latin is to remain the language of the Roman Rite, the constitution states: "But since the use of the vernacular, whether in the Mass, the administration of the sacraments, or in other parts of the liturgy, may frequently be of great advantage to the people, a wider use may be made of it, especially in readings and directives, and in some prayers and chants." (SC 36.2)

Supervision of translations is to be given over to national or regional episcopal conferences (SC 22.2), as well as the decision as to the extent of the translations. (SC 36:3-4) The subsequent fortunes of this issue will be dealt with below in an upcoming column.

With regard to the Eucharist, the constitution further specifies what parts of the Mass might be translated into the vernacular: "A suitable place may be allotted to the vernacular in Masses which are celebrated with the people, especially in the readings and 'the common prayer'; and also, as local conditions may warrant, to those parts which pertain to the people, according to the rules laid down in Art. 36 of this Constitution. Nevertheless, care must be taken to ensure that the faithful may also be able to say or to sing together in Latin those parts of the Ordinary of the Mass which pertain to them. Wherever a more extended use of the vernacular in the Mass seems desirable, the regulation laid down in Art. 40 of this Constitution is to be observed." (SC 54)

Many critics regarded the post-conciliar implementation of the constitution, especially on matters like the vernacular a betrayal, but despite what they contend, the last sentence demonstrates that latitude with regard to the extent of translation can be found in the document itself. This is not to say, however, that the issue of the vernacular was not hotly debated on the council floor. But even before the council ended in 1965, several national bishops' conferences were petitioning the Vatican for a very extensive translation of the liturgy into modern languages.

But translation of the liturgy was by far not the only practical principle of reform. A good deal was to follow ...

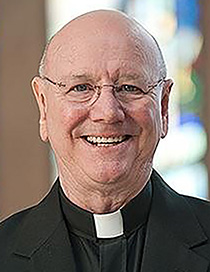

- Father John F. Baldovin, SJ, is professor of Historical and Liturgical Theology at Boston College School of Theology and Ministry.

Recent articles in the Faith & Family section

-

Did you know?Father Robert M. O'Grady

-

Sowing the Seeds of FaithMaureen Crowley Heil

-

Bread left overScott Hahn

-

Scripture Reflection for July 28, 2024, Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary TimeJem Sullivan

-

What the universal call to holiness entailsDr. R. Jared Staudt