Cardinal speaks on abuse crisis, need to 'rebuild trust'

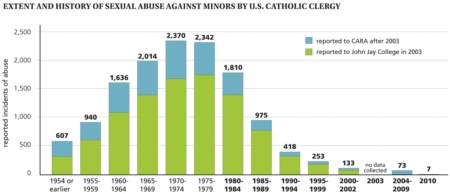

SOUTH END -- On Jan. 6, 2002 the Boston Globe began a series of articles revealing that archdiocesan officials reassigned Father John Geoghan to parish ministry even after it was known he had abused children in former assignments, sparking public outrage.

Over the next 12 months, the court-ordered release of personnel files led to the revelation of numerous other past allegations of abuse of minors by priests and, ultimately, to the resignation of Cardinal Bernard Law on Dec. 13, 2002. By then, what had become known as the clergy sexual abuse crisis had spread to dioceses throughout the United States and prompted the U.S. bishops to implement new policies for the protection of children.

In July 2003, Blessed Pope John Paul II appointed Cardinal Seán P. O'Malley, OFM Cap. as Archbishop of Boston. Cardinal O'Malley came to Boston with a reputation as a healer after having been appointed bishop of the neighboring Diocese of Fall River in 1992 in the aftermath of a highly publicized case of a priest abusing minors, the case of Father James Porter.

The Pilot spoke to Cardinal O'Malley Jan. 2 about 10th anniversary of the abuse crisis, its ongoing effects and efforts to rebuild trust in the Archdiocese of Boston and the wider Church.

Q. With the Porter case in 1992, you were probably the first bishop who was sent to a diocese to heal a very public case of sexual abuse of a large number of minors by a priest. How did that case prepare you for Boston?

A. Well, prior to Fall River I really did not have any experience, so it was an opportunity for me to become acquainted with the problem of pedophilia and child abuse. It made me very aware of the need to have very clear policies that would be transparent, and that everyone would be aware of. In Fall River, when we were developing the policies, I even printed them in the diocesan newspaper to ask people to comment on them and to give suggestions.

It was a steep learning curve but the situation was such that I went to Fall River realizing that my first priority had to be dealing with the sexual abuse crisis and trying to bring healing to the people and to develop policies that would allow the Church to move forward and make it a safe place for children.

Q. Ten years after the scandal broke in Boston, how do you explain the actions, or inactions, of Church officials who did not act swiftly when credible accusations of abuse were reported, often repeatedly?

A. As we say, hindsight is always better than foresight. In today's world we have an awareness of the great harm that is done to victims of child abuse. In the past, I fear, that was not the case. People did not realize how profound the harm was that was visited upon children. The harm, I think, was compounded when the perpetrator was a priest because of the identification of the priest with God, with the sacred, and, therefore, besides the psychological damage it also did grave spiritual damage.

But I think there was a lot of ignorance of these kinds of things. It became clear to me that, in the case of Father Porter, the bishop at the time, every time there was a complaint, he sent him to a mental health facility and there the psychologists were telling the bishop that he was cured, that he could be returned to (ministry) -- absurd things -- but at the time even the psychologists were giving that kind of advice. So I think all that contributed to the terrible decisions that were made.

There was also an exaggerated fear of scandal and trying to protect the institution. And I think, too, just in the culture at the time there was a lot of denial of this problem. People did not speak of these kinds of things -- ever -- even though it was like the elephant in the middle of the living room. I think we see reflections of that in the reporting on the case in Pennsylvania, where people just didn't want to deal with it, didn't want to face it. Even though they saw it, they were denying it. There was an unwillingness to grapple with the ugliness of this problem.

Q. Some are arguing that the archdiocese should not be marking this anniversary as we should have already "moved on" and it opens healed wounds. Why is it important that we are speaking about this now?

A. I think that the commitment of the archdiocese to work for the protection of children is an ongoing commitment. Often times we memorialize the tragic events in history so that they will not happen again. I think that this is one of those kinds of things.

Q. Cardinal Law became a lightning rod and resigned 11 months into the scandal. Do you think it was the right decision?

A. Definitely I think it was the right decision. It was the right decision for Cardinal Law to submit his resignation and the right decision for the Holy See to accept it. It was becoming increasingly more difficult for him and the Church and it was necessary. Certainly, one of the things the Church grapples with today is accountability on the part of bishops, but in this case we see that there was a realization of the seriousness of the situation and the egregious nature of the mistakes that had been made and the pastoral necessity of a change in leadership.

Q. As soon as you arrived in Boston, you were able to settle a large number of cases in less than two months that the previous administration had been unable to resolve. What changed?

A. I brought the advantage of having some experience in Fall River and was able to bring attorney Tom Hannigan on board, who shared a lot of my pastoral concerns for the way that victims needed to be indemnified. We tried to develop a system that depended on arbitration so the Church would not be involved in trying to assign particular amounts for different kinds of damages, but rather people who were judges and had experience in these kinds of things would be the ones to work out global settlements. That allowed us to settle a large number of cases.

So, putting a certain amount of money aside and allowing arbitrators to make the distribution did help to remove the Church a little bit from these kinds of situations; that I think allowed us to take a more pastoral relationship with the victims and their families.

Funding for the settlements was always a concern for us because we did not want to use parish or appeal funds to resolve the legal cases against us. Our options were very limited and we decided that the best way to settle those claims was by the sale of the archbishop's residence and adjoining property in Brighton. It had a historical value, but it was not essential to carry out our mission and gave us the opportunity to have a very transparent way of paying for the settlements.

Q. In these years, you have met with hundreds of survivors. How have those meetings -- and the stories told in them -- affected your views about the gravity of the abuse of children?

A. It has made me very acutely aware of the effects that abuse has not only on the individuals but on their families, on the community, the long-range kind of damage that people suffer because of this and particularly, in the case of clerical sexual abuse, the damaged relationship with the Church, with God, and their spiritual life.

Q. You were the first bishop who brought survivors of sexual abuse to meet with the Holy Father. Why did you do it and do you think he was moved by this?

A. At the time of the Holy Father's visit to the United States, there was a lot of controversy over the decision not to include Boston in the cities that the Holy Father visited. Many people alleged that this was because the Holy Father wanted to avoid the whole "problem" of sexual abuse.

I suggested to the Holy Father that it would be important for him to meet with victims and he agreed with me.

We were able to make the arrangements in such a way that people came with us to Washington and met with the Holy Father in the chapel of the nunciature without the press knowing ahead of time because we didn't want a circus-like atmosphere. We presented the Holy Father with a book containing the names of all those victims of clerical abuse that we were aware of in our archdiocese. We asked the Holy Father to pray for them and their families.

The Holy Father had a personal exchange with each of the victims that we took with us. It was a very moving experience and I think it helped to contribute to the success of his visit to the United States.

Q. In Boston, we have had a number of falsely accused priests. How do you feel about the harm that this crisis has done to priest morale?

A. I think that there is always a danger of a false accusation. I think they have been few and the establishment of an independent review board has given us a good instrument to be able to have outside people look at these cases and help us determine what accusations are unsubstantiated in such a way that we can return a man to ministry with the assurances to our people that an independent group of competent professionals -- people who were themselves either victims of sexual abuse as children or parents of victims, psychologists, judges, lawyers and canonists -- have looked at this and have helped us to make a decision that this priest can be returned to ministry. And our experience in general, with very few exceptions, is that when priests are returned to ministry that the people accept them and they trust the decisions that have been made.

Obviously, that doesn't take away the pain, embarrassment and psychological damage that's done by a false accusation. But, one of the advantages of the use of the review board and the zero tolerance policy is that when a priest is returned to active ministry, Catholics understand that the Church has judged this man to be innocent and apt for ministry.

Q. Some are advocating for a relaxation of the "one credible accusation" rule for taking a priest out of ministry. Do you think it is time to do that now?

A. I think that in order to be able to rebuild trust, the Church cannot go back on this policy. To rebuild trust and to guarantee the absolute protection of children is the reason why this is being done. Sometimes there is only one accusation we know about but that doesn't mean it's the only one. And, even if it is the only one we know about, it still has caused damage and the Church needs to be very strict in this area.

There are other areas perhaps were a person can be rehabilitated but [not after child abuse].

Q. Bishops have been saying for years that the sexual abuse of minors is a societal problem, and recent allegations at Penn State or at public schools seem to confirm that view. What should be done to increase the public's awareness of the pervasiveness of sexual abuse in families, schools, summer camps and other instances where minors are in contact with adults?

A. I had hoped that all the publicity around the problem of sexual abuse the Church would have brought about a conversation in society that has not happened. The focus has been so strong on the Church that it fails to contextualize the broader problem but we hope that of all our efforts -- screening and education -- can be helpful to other institutions and churches and organizations as they grapple with the same problems.

Q. Episcopal responsibility for mishandling of abusers is a pending subject, according to some survivors' groups. Do you think more should be done about that?

A. I think it's something that the Church needs to look at more carefully.

Certainly, since the establishment of policies, that if bishops are negligent now the Church needs to act because there can be no excuse now that people did not know or realize the gravity of the situation. Of course, these are decisions of the Holy See. Bishops conferences and individual bishops are not competent to remove a bishop or to demand his resignation. It can be a counter witness if the Church does not take this seriously in dealing with situations where a bishop has been criminally negligent.

Q. You have been advocating with the Holy Father and your brother cardinals for global measures to fight sexual abuse of minors by priests that may take the U.S. charter for the protection of children as a model. How has been the reception of those comments?

A. At the last consistory many cardinals came up to me afterwards and expressed that they wanted copies of what I had said, and said they were interested. When I addressed the Capuchin bishops at San Giovanni Rotondo last September, the father general was there and he told me he would bring it up in our next chapter to make our friars more aware of our obligations to have policies in place. And the Holy See itself has issued instructions to all the bishops' conferences that, during the course of this year, they should come up with norms that will be then sent to the Holy See for revisions.

So I think a lot is happening and the Church is becoming more aware of the global aspects of this and the need to address it. The problem is that in many of the countries where there are such limited resources it's a big challenge but it needs to be a very important part of the way we conduct business in the third millennium.

Q. After 10 years is the Catholic Church a safer place for children?

A. I don't know of any other institution that does nearly as much as the Catholic Church to safeguard children. All human endeavors are fallible, but certainly the screening, the training, the kinds of policies that are in place and the annual audit that is in place that looks in our parishes and institutions to ensure they are following the policies carefully and bring to our attention any areas that need to be improved, I think all of this and the thousands of people who are involved in the Archdiocese of Boston in child protection is something that no other institution is doing.

When some of the pastors came to us and said they didn't need child protection as part of the CCD program because the children were in public schools, we checked and we found the public schools were not doing anything. So, it's obvious that no one is doing what the Catholic Church is doing now. It is sad that it took the scandal to galvanize us to do this, but God brings good out of evil and I think the good is that our Church today is safer than it's ever been for children and young people.