The admission of torture

There seems to be no argument over whether the Central Intelligence Agency used brutal and harsh means in pursuit of its goal of extracting information from imprisoned and detained terrorism suspects for years after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the U.S.

Waterboarding, wall-slamming, sleep deprivation and other assaults on human dignity are euphemistically bundled under the banner of "enhanced interrogation techniques." There is no doubt in my mind that the CIA used torture, although the agency's defenders shy away from use of that word.

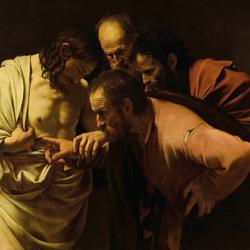

Regardless of the choice of vocabulary, the question of whether the end justified the means cannot be ignored. The absence of the word "sin" in all of the commentary that has followed the release on Dec. 9 of the Senate Intelligence Committee's sweeping indictment of the CIA's behavior might be dismissed as quaint, but is surely curious and worthy of comment.

Where did the waterboarders, wall-slammers and assailants of human dignity get their moral formation? Just a few years earlier, they occupied space in our classrooms, places in our pews, seats at our dinner tables and positions on our school athletic teams. Was morality ever discussed? Were rules ever explained? What explanation can be given for the evolution of a brute in America today?

The late Japanese novelist Shusako Endo offers in a novel titled "Silence" a directional signal for anyone in search of an explanation. Endo was Japan's foremost novelist in the 20th century. "Silence" is considered to be his masterpiece. The novel tells the story of a 17th-century Portuguese Jesuit missionary priest in Japan at the height of the fearful persecution of the small Christian community. The protagonist is arrested and taken prisoner and pushed into a little hut.

The novel includes this passage: "He could hear the muffled voices of the chattering guards outside. Sitting on the ground and clasping his knees ... he was drawn by the voices of the guards outside the hut. What was so funny that they should keep raising their voices and laughing heartily? His thoughts turned to the fire-lit garden [scene of the agony in the Garden of Gethsemane] and the servants; the figures of those men holding black flaming torches and utterly indifferent to the fate of one man [Jesus]. These guards, too, were men; they were indifferent to the fate of others. This was the feeling that their laughing and talking stirred up in his heart."

His musings revolved around their hardness of heart. And Endo puts these thoughts in his mind: "Sin, he reflected, is not what it is usually thought to be; it is not to steal, and tell lies. Sin is for one man to walk brutally over the life of another and to be quite oblivious of the wounds he has left behind."

And there you have it, the obliviousness, the hardness of heart, the brutality that marks the abandonment of humanity and the presence of sin.

Call it an "enhanced interrogation technique," if you will, but there is no getting around the fact that the sin of torture is on the American conscience now and the least we can do is name it and admit it, and give more than a passing thought to repentance.

---

Jesuit Father Byron is university professor of business and society at St. Joseph's University in Philadelphia.

- Father Byron is a columnist with the Catholic News Service.