Indiana poet seeks healing from clergy sexual abuse through his works

INDIANAPOLIS (CNS) -- Norbert Krapf, 71, still loves the wooded hills of his southern Indiana boyhood home near Jasper and the Catholic faith that formed his beliefs from infancy.

Such feelings are remarkable not for their longevity, but that they exist despite Krapf being the victim of clergy sexual abuse six decades ago at his small hometown parish tucked away in the Jasper hills.

In recent years, Krapf -- a poet, author and one-time Indiana Poet Laureate now living in Indianapolis -- identified his abuser to the bishop of the Diocese of Evansville in which Jasper is located, leading to the removal of the deceased priest's many accolades and honors.

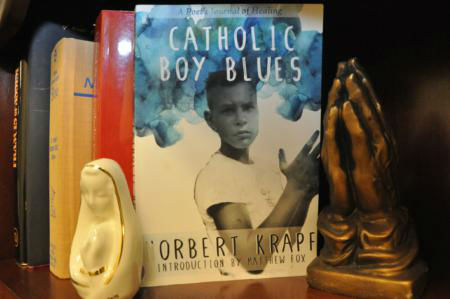

But Krapf then took a much bigger, public step. Using his gift for poetic expression, he published "Catholic Boy Blues," a book of poems dealing with the abuse through the voices of the suffering boy, the coping adult, the wise Mr. Blues and the abusive priest.

The book, along with Krapf's other works, helped earn him the 2014 Eugene and Marilyn Glick Regional Author Award.

More importantly, it has been instrumental in Krapf's own healing and, he hopes, the healing of other sexual abuse victims.

Of Krapf's 26 published books, 11 are works of poetry. Many of the poems revolve around his southern Indiana roots, his love for the wooded hills he explored as a child and his German heritage.

He and his family were members of Holy Family Parish in Jasper, with Msgr. Othmar Schroeder serving as pastor. The priest, who died in 1988, was a family friend, spiritual director of Krapf's father, trusted role model in the parish -- and a sexual predator of boys.

On weeknights before an early morning Mass, Krapf told The Criterion, newspaper of the Indianapolis Archdiocese, "(Msgr. Schroeder) would have us (altar servers) stay over, and that's when the abuse took place. There probably were as many as 50 victims in my parish."

Krapf learned to keep silent about the abuse. Msgr. Schroeder was respected in the community, a theme repeated in many of the poems in "Catholic Boy Blues." In one poem, "Once Upon a Time a Boy," Krapf describes the beating a friend received when the boy told his father about the abuse.

"It's a survival mechanism," he says of the silence. "If you focused on that (abuse) as a child, you wouldn't be able to function. You would just go to pieces, do some damage to yourself. I did some heavy drinking in the summers when I came home from college and worked across the street from where the abuse took place."

So Krapf remained silent and went on with life. He considered becoming a mechanical engineer until he "fell in love with poetry" during his senior year in high school. He earned a bachelor's degree in English from St. Joseph's College in Rensselear, Indiana, and his master's in English and doctorate in English and American literature from the University of Notre Dame.

At the university, he met his wife, Katherine, who had left the Carmelite order and was completing graduate studies.

It was also at Notre Dame that Krapf developed a love for blues music. That musical expression would later help shape some of the poetry that led to his healing in "Catholic Boy Blues."

Krapf and Katherine moved to New York City in 1970, where he taught at Long Island University and directed the C.W. Post Poetry Center, and Katherine taught middle school English.

Meanwhile, except for confiding in Katherine, his silence continued.

"I just had to be ready for (facing) it, and I wasn't," Krapf says. "Part of it was teaching full time" and raising the two children he and Katherine adopted from Colombia.

It was the children who helped bring Krapf back to the Catholic faith he had distanced himself from as an adult.

"Katherine said she wanted to give them a good religious background and tradition, and it seemed like a good idea," he says. "But it was very difficult for me."

The couple retired from teaching and moved to Indianapolis in 2004. They settled into a townhome a few blocks from St. Mary Parish, where they have been members for 10 years.

In 2006, the incidents of Krapf's past began to haunt him.

"There was a priest ... I read about who had been moved from one parish to another, three different parishes, abusing boys," Krapf recalls.

One parish to where the priest was relocated was not far from where Krapf grew up. He told himself, "I have an obligation to do something about this."

He wrote a letter to Bishop Gerald A. Gettlefinger, then-bishop of Evansville. The bishop called just two days after the letter was mailed.

Krapf met with the bishop and in 2007, Bishop Gettlefinger had made the priest's abuse public. Honorary photos of Msgr. Schroeder were removed from Jasper churches, and a Knights of Columbus council named in his honor was asked to change its name. The diocese offered to pay for counseling for victims of priest abuse.

Krapf was pleased by the moves but was far from healed. The case of the priest who was moved around several Indiana parishes continued to bother him so he turned to Father Michael O'Mara, St. Mary's pastor at the time.

"He said, 'You know, Norbert, I'm a victim of this, too. Whenever we have family gatherings, and parents have their young boys with them, they kind of look at me funny, like they wonder, "Is he ... ? Does he ...?"

"He was enormously sympathetic," Krapf says.

The last poem in "Catholic Boy Blues," "Epilog: Words of a Good Priest," is dedicated to Father O'Mara.

Krapf also discussed the abuse with a spiritual director, who prompted him to address his past through poetry. So Krapf began to write -- and write, and write.

"I wrote 325 poems in just one year," he says. "And then I wrote another 50 after that."

Krapf gave himself several years to edit the poems and develop the book, which he described as "a calling."

Before the publication of "Catholic Boy Blues" in April, Krapf notified Indianapolis Archbishop Joseph W. Tobin.

"I offered to send him a proof of the book in case he wanted to be prepared," Krapf says. "He wrote a very warm, gracious reply."

Archbishop Tobin's support went beyond words. He offered an opening prayer at Krapf's first book signing, and he sent a copy of the book to Pope Francis.

"A reading of 'Catholic Boy Blues' permits one to glimpse the incredible pain of victims of sexual abuse," Archbishop Tobin told The Criterion. "The fact that such abuse occurred during the victim's childhood and was inflicted by a priest, that is, a person whom a child would instinctively trust, makes the pain even more hideous.

"Yet the spirit of Norbert Krapf emerges from this terrible crucible to offer a testimony to the power of God to bring light out of darkness and, finally, life from death.

"I thank God that Norbert and Katherine have found healing and are willing to serve as instruments of healing for others."

That healing can be quantified.

"That night of the book launch ... I don't even remember how many people thanked me because either they were a survivor, or someone in their family or a friend (was a survivor)," Krapf recalls. "There's been a strong outpouring of support."

Krapf is exploring ways to bring the message of hope and healing in "Catholic Boy Blues" to groups through poetry readings and collaborative presentations.

A recurring question Krapf says he receives at book signings and poetry readings is how he can stay in a church that caused him so much pain.

"I tell them that I don't feel that way," he says. "I recognize that a big part of me is Catholic. I have a sense that this is my church, and I'm not going to let it be taken away from me, and I'm going to help improve it.

"That might seem like a delusion of grandeur, but I believe it."