The Mercy That Prepares Us for the Mercy of the Eucharist

The celebration of the Eucharist, in words made famous by the Second Vatican Council, is the "source and summit," the font and apex, the alpha and omega of the Christian life. It's the starting point from which everything in the Christian life flows and it's the goal toward which everything goes.

Therefore the Eucharist must likewise be the root and fruit of the extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy.

This truth makes Sunday's celebration of Corpus Christi, the Solemnity of the Body and Blood of the Lord, extraordinarily special.

There's a deep, intrinsic connection between God's mercy and the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist.

When Jesus consecrated the chalice of his Precious Blood, he said he was explicitly doing so "for the remission of sins."

In the Divine Mercy devotion, the apparitions of Jesus to St. Faustina in the 1930s that the Church has found worthy of belief, Jesus asked us to offer to the Father his "Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity, in atonement for our sins and those of the whole world."

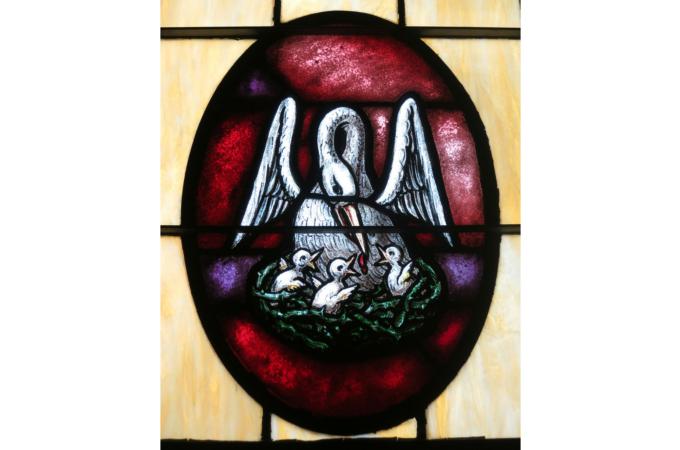

St. Thomas Aquinas, in his famous Adoro Te Devote, written by papal commission for the first celebration of Corpus Christi in 1264, beautifully commented, "O Lord Jesus, Holy Pelican, cleanse me totally clean with your blood, one drop of which is enough to save the whole world from every sin." In Medieval symbolism, the Pelican willingly rips open her breast and bleeds to death so that her children may live off her blood, and St. Thomas says Christ did that for us to redeem us from our sins and ensure our eternal survival, highlighting the connection between God's mercy and his Eucharistic self-giving.

St. John Paul II emphasized in his 2003 encyclical on the Eucharist that "the two sacraments of the Eucharist and Penance are very closely connected" and Pope Benedict in his 2007 Eucharistic exhortation added that "love for the Eucharist leads to a growing appreciation of the Sacrament of Reconciliation."

This connection was illustrated in a particularly beautiful and poignant way in the life of the patron saint of priests, St. John Vianney, who heard Confessions 12-18 hours a day for 31 years so that, he said, his people and penitents from all over 19th century France would be able worthily to receive Holy Communion. And that connection between these two Sacraments is reemphasized in the ministry of confessors today the world over.

Pope Francis has himself stressed that the Eucharist "is not a prize for the perfect, but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak." The Eucharist is itself a Sacrament of Mercy, strengthening us from the inside to live our life in loving communion with Christ and helping us to make our life truly Eucharistic, so that with Christ we may "do this in memory" of him, offering our own body, blood, soul, sweat, tears, work, and all we are and have out of love for God and others.

St. John Paul II reminded us, however, of the perennial teaching of the Church, that "the celebration of the Eucharist, however, cannot be the starting-point for communion; it presupposes that communion already exists, a communion that it seeks to consolidate and bring to perfection." The Eucharist requires that it be "celebrated in communion," by someone persevering "in sanctifying grace and love, remaining within the Church 'bodily' as well as 'in our heart.'" Reaffirming the clear teaching of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the saintly pontiff stated, "Anyone conscious of a grave sin must receive the Sacrament of Reconciliation before coming to communion."

It's important to underline this intrinsic connection between the Sacraments of Penance and the Eucharist because, as Pope Benedict wrote in 2007, we are "surrounded by a culture that tends to eliminate the sense of sin and to promote a superficial approach that overlooks the need to be in a state of grace in order to approach sacramental communion worthily."

It would be a severe failure in mercy, a gross spiritual malpractice, for the Church not to stress this perennial doctrine and discipline: that before one receives Jesus Christ in Holy Communion one must be in communion of life, restored often by God's mercy in the Sacrament of Penance.

The reason behind this truth was stressed by St. Paul when he declared, "Whoever eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord unworthily will have to answer for the body and blood of the Lord," in other words, for the Lord's death. Since to receive Jesus unworthily is sinful and Jesus died for our sins, anyone who received Jesus unworthily is guilty of his death. Therefore, the Apostle warned, "A person should examine himself, and so eat the bread and drink the cup. For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the body, eats and drinks judgment on himself" (1 Cor 11:27-29).

St. Thomas Aquinas harrowingly illustrated St. Paul's point in the Lauda Sion Salvatorem Corpus Christi sequence Catholics will sing this Sunday, reminding us that the "Bread of Life" (Jn 6:48) becomes the bread of death for those who consume Jesus in the state of sin.

"Sumunt boni, sumunt mali, sorte tamen inaequali, vitae vel interitus. Mors est malis, vita bonis: vide paris sumptionis quam sit dispar exitus," the Doctor of the Church insisted. "Both good and bad receive, but to unequal ends, one to life and the other to the tomb. Death to the bad, life to the good; behold how different the outcome of a similar ingestion."

When one receives unworthily, the Sacrament becomes a sacrilege; the spiritual medicine becomes for that person -- it's shocking to say -- a form of spiritual poison.

Receiving Holy Communion is meant to be the consummation of the loving union between Jesus the Bridegroom and his Bride the Church (and the individual bride, a human soul), when the Bride takes within her the Body of the Bridegroom and becomes one flesh with Him. Similar to relations between a man and a woman, however, what is meant to be an act of mutual love and sanctification becomes seriously sinful when the man and woman haven't been joined by God in a one-flesh loving communion.

An analogous sin of existential incoherence happens with those who receive Jesus without already being joined to him in a communion of grace in life, who do not have the intention to leave sin behind and faithfully persevere in saying "I do!" in total sacramental, doctrinal, and moral union of life with Christ.

In an age in which many approach Holy Communion superficially, akin to receiving birthday cake at a birthday party, this teaching of the Church might seem "unwelcoming" or lacking in mercy.

But it's actually the pinnacle of mercy.

The Church invites everyone to the Banquet, per Jesus' famous Parable (Mt 22:12), while at the same time committing herself to helping everyone arrive properly dressed, restored to their Baptismal garments -- lest the greatest Gift of all serve to their ruin rather than resurrection.

It's this intrinsic requirement for one to be in the state of grace to receive the Sacrament of the Eucharist worthily that helps all those who desire to receive Jesus in Holy Communion appreciate more deeply and avail themselves more frequently of the Sacrament of Penance. It's through the Sacrament of Mercy that "Mercy incarnate" himself prepares us to receive him through the hands and prayers of the same priests through whom he gives us his Body and Blood.

Just as Jesus at the beginning of the Last Supper washed the feet of his disciples and cleansed them of the filth that had accumulated through contact with the world, so he continues to wash us in the Sacrament of his Mercy of any filth accumulated since the bath of Baptism.

This is the means by which he out of love helps us participate fully and worthily in the Sacred Banquet of his Body and Blood.

- Father Roger J. Landry is a priest of the Diocese of Fall River, Massachusetts, who works for the Holy See’s Permanent Observer Mission to the United Nations.