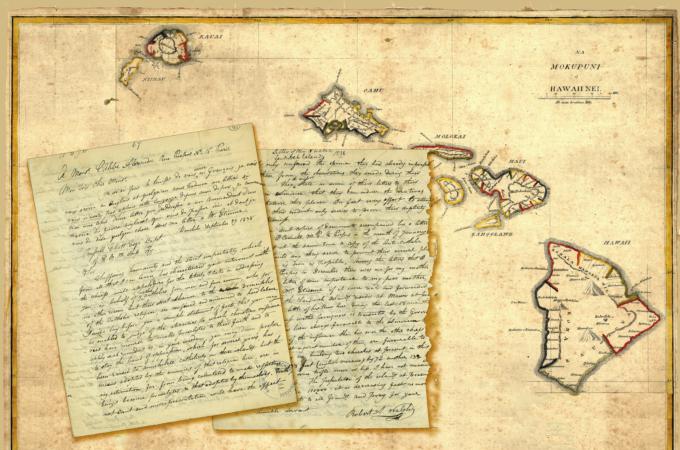

Letters from an early missionary to the Hawaiian Islands

Within the archive reside several documents speaking to the struggles of the earliest Catholic missionaries to arrive in the Hawaiian Islands.

After a series of inter-island conflicts, the Hawaiian Islands were united under one ruler, Kamehameha I, around the beginning of the 19th century. Shortly afterward, in 1820, the first Protestant missionaries are believed to have arrived from New England. They proved effective in converting the native population, so much so that when the first Catholic missionaries appeared in 1827, they were persecuted and forcibly removed from the islands.

These early Catholic missionaries consisted of six members of the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts in France and were led by Sister Alexis Bachelot. Despite this setback, she would seek out an ally in the French government to help negotiate the freedom of religion on the Hawaiian Islands, which was granted in 1839.

In the intervening years, a few Catholic missionaries were allowed to remain under the condition that they not proselytize the native population. One of these was Father Robert A. Walsh, several of whose letters survive in the archdiocesan archive.

The first dates to Sept. 10, 1838, in which he writes to his superior in Paris, revealing the nature of the persecution against Catholics in the region.

He writes: "I will lay before you a simple statement of facts, that you may be enabled to judge of the atrocities to which Christian missionaries have recourse to make proselytes to their faith and to apply such remedies as, in your wisdom, you may deem proper to stay the hand of oppression."

He then reveals the fate of nine native converts, five men and four women, who were being punished for living the Catholic faith. Two of them, a husband and wife, had been imprisoned at a fort for three years, periodically being forced to remove human waste from the fort using only their bare hands. Of the others, the husbands and wives were separated, and the latter taken away to build a public road; they had since been reunited but are punished with physical labor.

While he "will not dwell any longer on this heartrending scene," he remains hopeful that these conditions will lead to the making of "sincere converts" to the Catholic faith, as only those who really see the truth will heed the call of the Catholic missionaries knowing what might lay before them.

Finally, he relays a story of his conversations with the captain of The Fly, a ship which passed through the area. Hearing of the persecution of Catholics, he appealed to Protestant authorities for their help, and while they claimed Catholics violated Protestant laws because they were idolaters, the resulting punishments could not be avoided as they were laws of the Hawaiian government. Father Walsh admits that while this was true, the Protestant missionaries carried great influence and could advise the government to be more lenient, should they choose.

Father Walsh writes again the following month, indicating he is disappointed not to have received any letters, but realizes he may receive news after writing. He discusses a visit by The Fly, perhaps the one alluded to in his earlier letter, where he was invited on board the ship and treated very well by those aboard. They were interested in the persecution of Catholics, and he appeased them, speaking at length about Sister Bachelot and the native converts.

The final letter, in French, dates to November 1838. Father Walsh declares himself a hermit, revealing he rarely leaves home due to the restrictions placed upon Catholic missionaries. When he does leave, it is frequently to walk in the adjacent garden, or to visit the English Consul, whom he believes has no sympathy for the plight of Catholics in the region. He was encouraged by news from passing ships that there were other islands where Catholic missionaries would be able to settle, and encourages his fellow brothers and sisters to set up missions at these locations, believing it will not be hard to find willing converts among the native people there.

- Thomas Lester is the archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston.