Church's stance on organ donation

Q. What is the Catholic Church's position on donating body parts for medical science? (Northampton, Pennsylvania)

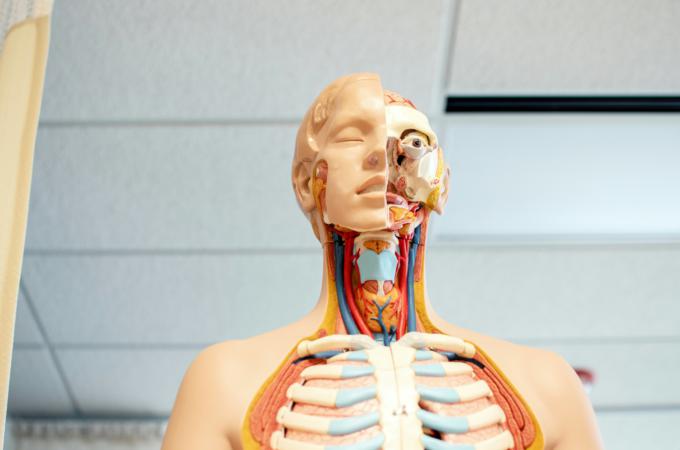

A. Let's divide the answer into two parts: post-mortem transplants and those from living donors. Gifts from a donor who has clearly died -- either to a living recipient or to scientific research -- is the easier part.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church says: "Organ donation after death is a noble and meritorious act and is to be encouraged as an expression of generous solidarity" (No. 2296). The Church does teach that the remains, after organ donation or medical research, should be treated with reverence and should be entombed or buried.

As to gifts from living donors -- bone marrow, say, or a lung -- this is morally permissible so long as it is not life-threatening to the donor and does not deprive the donor of an essential bodily function and provided that the anticipated benefit to the recipient is proportionate to the harm done to the donor.

In his 1995 encyclical "The Gospel of Life," St. John Paul II called organ donation an example of "everyday heroism," and in 2014, Pope Francis told the Transplantation Committee for the Council of Europe that organ donation is "a testimony of love for our neighbor."

Q. Why are Catholic churches muzzled while Protestant churches freely exercise political speech through endorsements, hosting candidates, etc.? This does not seem equitable. (Hilliard, Ohio)

A. The laws are the same for all churches. The ban on political campaign activity by charities and churches has been in effect for more than half a century.

It was created in 1954 when Congress approved an amendment proposed by Sen. Lyndon B. Johnson that prohibited tax-exempt entities (technically 501©(3) organizations, which includes charities and churches) from engaging in any political campaign activity. (In 2000, in a case called Branch Ministries v. Rossotti, the U.S. Court of Appeals upheld the legality of that ban.)

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops periodically reminds churches and church leaders of the implications of that ban. In a website article called "Do's and Don'ts Guidelines During Election Season," the USCCB lists among activities to avoid: "Do not endorse or oppose candidates, political parties or groups of candidates, or take any action that could reasonably be construed as endorsement or opposition." The bishops' conference also warns parishes that they should not "invite only selected candidates to address your church-sponsored group."

While churches are prohibited from endorsing candidates, this does not prevent them from speaking out on moral issues, even if these happen to be interwoven with political topics -- issues like care for the poor, religious freedom, human life and migration.

At times, I have seen certain religious leaders try to differentiate, claiming that in endorsing a particular candidate, they were simply expressing a personal preference and not speaking as a church representative. But that, in my mind, is dangerous turf and could well be "reasonably construed" as institutional endorsement.

What our letter writer mentions does in fact happen, and I believe that it may be due -- in part, at least -- to the fact that Protestant and evangelical churches sometimes lack the central oversight that guides Catholic parishes.

I also believe that a distancing from political endorsements is preferred by over 50 percent of Catholics -- and that has been documented in a 2014 study by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. And interestingly, Canon 287 of the church's Code of Canon Law says that clerics "are always to foster the peace and harmony based on justice" but "are not to have an active part in political parties."

- Father Kenneth Doyle is a columnist for Catholic News Service