Reissued biography shows saint's complexity, contradictions

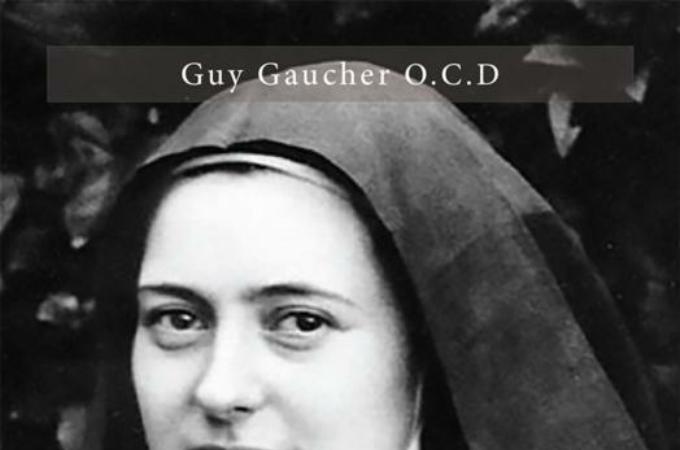

"Saint Therese of Lisieux: Story of a Life" by Guy Gaucher, OCD. Ignatius Press (San Francisco, 2019). 275 pp., $17.95.

Bishop Guy Gaucher argues that few saints have been as misunderstood in their lifetime as much as St. Therese. Worse, she was victimized by the saccharine religiosity of the late 19th century.

In his book, "Saint Therese of Lisieux: Story of a Life," Bishop Gaucher offers a realistic portrayal of the French saint as opposed to the mawkish one often associated with her.

Considered the foremost Theresian scholar, Bishop Gaucher (1930-2014) was a Carmelite friar and an auxiliary bishop of the Diocese of Bayeux and Lisieux. Editor of St. Therese's complete works, he wrote the original edition of this biography -- considered the premier biography -- of one of the world's best-loved saints. Ignatius Press is issuing a new edition of this book, which has long been out of print.

Written in an accessible style, Bishop Gaucher's biography essentially gathers the pieces of Marie Francoise-Therese Martin's life and puts them into narrative order, referencing her exercise books, poems, prayers, religious concepts, notes and letters. It would have been helpful if he had discussed the controversy surrounding her canonization, which occurred in 25 years, a process that normally takes longer, but, as he writes, covering everything that happened after her death would have taken a whole other volume.

He includes about 10 pages of testimonials, selected from "tens of thousands." Some of these instances were declared miraculous, including those required for her beatification and canonization.

As Bishop Gaucher presents Therese, she was a woman of contradiction and complexity. She was just 15 when she joined the Order of Discalced Carmelites. She disliked pretense but sometimes seemed pretentious; she had an intellectual approach to the Bible, but would open the Bible at random to find a quote that she took as a sign of divine intervention; she loved Mary but didn't particularly like saying the rosary.

Therese suffered from scrupulosity yet had a mystical love for Jesus Christ. Inspired by the Song of Songs, she wrote poems about her love. She also was capable of prodigious love for people, which showed in her kindness to others or in what she called her "little way." Her sister, Marie (also a Carmelite), believed that Therese was possessed by God. Therese thought that she spoke to Jesus and that he responded to her. But then, he left her or seemed to.

The book's most affecting section discusses Therese's doubts. She felt Jesus had abandoned her to a dark nothingness. As Bishop Gaucher puts it, "horrible inner voices suggested to her ... that her whole spiritual life had been illusion. She was going to die young, for nothing." Her confessor advised her to write out the Apostles Creed and keep it with her. She wrote it using her own blood.

She related much of this in her memoir, "The Story of a Soul," which was not an autobiography so much as it was a collection of letters, notes, scraps and fragments. She wrote these jottings as an assignment from the prioress.

Because she had tuberculosis and was unable to polish her work, she gave her three biological sisters (also Carmelites) permission to do so. What they put together became an all-time best-seller which has been translated into numerous languages. The reception accorded to "The Story of a Soul" probably would have shocked Therese had she been alive. The book is still widely read.

Before she died at age 24, she promised to spend eternity helping people deal with the pangs of life and showering them with roses as a sign that she had heard their supplications.

People asked her to intercede for them with the divine, and there occurred what many call "the shower of glory," as thousands claimed she came to their aid. She wanted to love Jesus Christ and to inspire others to love him. She did not wish to call down any glory on herself.

But as Bishop Gaucher's biography skillfully demonstrates, glory came calling. Therese was beatified in 1923 and canonized in 1925. She was made a doctor of the church in 1997 -- only the third woman to be so named.

- - -

Scharper has written seven books and is a frequent contributor to America and the National Catholic Reporter.