Vatican astronomer shares insights at Harvard lectures

CAMBRIDGE -- Jesuit Brother Guy Consolmagno, director of the Vatican Observatory, is no stranger to the Boston area. A native of Michigan, he earned his B.S. and M.S. in planetary science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which, he said, he chose to attend because it housed the world's largest collection of science fiction. He visits Boston annually for the Boskone 56 Science Fiction Convention, according to Joshua Shutter, a Harvard Ph.D. candidate in chemical physics.

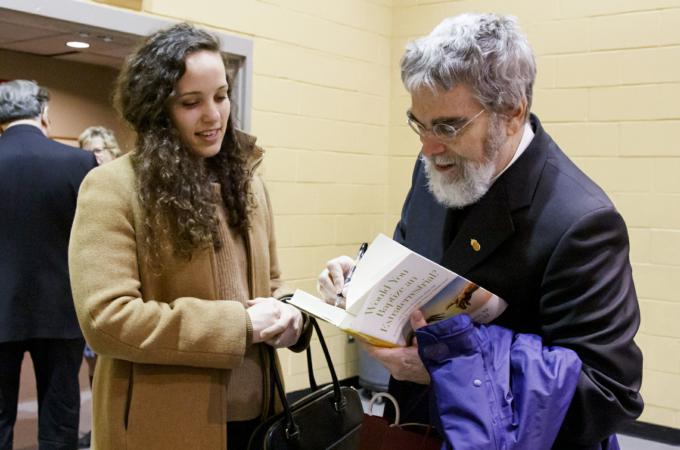

Professors Mark and Barbara Poliks from SUNY Binghamton connected Shutter with Brother Guy, who delivered two lectures to the Harvard community, "Adventures of a Vatican Astronomer" on Feb. 13 and "The Galileo Affair in Context" on Feb. 14. The Pilot attended the Feb. 13 lecture at St. Paul Church in Harvard Square.

Though scaffolding lined the walls of St. Paul Church, approximately 160 people -- parishioners, young professionals, Harvard University students and staff -- filled the available pews. In a presentation filled with anecdotes and punctuated by jokes, Brother Guy talked about the structure of the Vatican government, the role of the Vatican Observatory, the purpose of science, his career and vocational discernment, and the supposed conflict between science and religion.

Brother Guy said the Vatican Observatory began as a group of astronomers, most of them Jesuits, tasked with advising Pope Gregory XIII as he reformed the calendar in 1582. At the end of the 1800s, Pope Leo XIII formally re-founded the observatory, which was relocated a few times due to problems with light pollution that made observing the stars difficult in Rome. The observatory currently has its headquarters at Castel Gandolfo, 15 miles south of Rome, and has a research group and offices in Tucson, Arizona.

Brother Guy identified two reasons why the Vatican has an observatory: to show that the Church supports science and to show that the Vatican is an independent country with its own national observatory.

He recalled such "adventures" as visiting Hawaii to use a telescope, living in Antarctica for six weeks to collect meteorites, representing the Vatican to the United Nations, and meeting Pope John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI, and Pope Francis.

Brother Guy said that in his late 20s, as his doctoral fellowship at MIT dragged on, he wrestled with the question of whether his academic and scientific interests were worth pursuing.

He said that he wondered, "Why am I worried about mathematical models of the moons of Jupiter when people are starving in the world? Isn't this academic life a total waste of time? Aren't there more important things going on?"

He then decided to join the Peace Corps and was sent to teach in Kenya. During his training, he became so homesick that he considered asking to be sent home. Thinking it would be his last night in the equatorial country, he got up early to look at the constellations he had learned about from books as a child. When he spotted not only the constellations he had read about but also many he recognized, he realized he did not need to return to the United States to be home.

"Anywhere in the world where I can see the stars, I know I am home," he said.

He decided to stay in Kenya, where he taught at a high school and later became a professor at the University of Nairobi. When he traveled out of the city to get a good view of the stars, people in the villages would line up to look through his telescope -- and they all reacted with awe.

Brother Guy said that is what makes human beings different from animals.

"Human beings look at the sky and wonder. Human beings want to know, What is that? What have other people seen up there? How can I get in on the fun of being able to discover what's up there? Because that's what it means to be human as opposed to a well-fed cow," he said.

That is why universities exist, along with "all of those useless liberal arts that make us more than well-fed cows. Because human beings do not live by bread alone. I read that someplace," he joked with the audience.

He talked about his decision to become a Jesuit brother rather than a priest, and said that although he does not have the responsibility of pastoral care, his work still involves people.

"People are in everything I do. People are in the classes I teach. People are reading the papers I write. People are in the universities where I work. Astronomy is not the study of stars and planets. Astronomy is the study of how people have studied stars and planets. It's the history of who has written what paper, why did they have that idea, how did it turn out. Human beings are what make astronomy alive, and human beings are what makes the work we do, whatever that is, a work that is alive," he said.

Brother Guy said the perceived "war" between science and religion is "a 19th century invention," stemming from the then-growing belief that new discoveries and inventions would better humanity and eventually replace religion.

He said the misapprehension that science and religion contradict each other comes from a poor understanding of each discipline. He said most people stop learning science and religion around age 12 and think the subjects merely involve getting answers from different books.

"If religion is one big book and science is another big book and the two books don't agree, which book do you listen to? That's the conflict in a nutshell. But religion isn't a big book, or at least it's not a book that's been finished. Science isn't a big book. Science is not a book that's been finished. Science and religion are the dance we are having on the precipice of what we know to embrace what we don't know," Brother Guy said.

He encouraged any scientists present to make their profession known to their faith communities and let them know that they should not be afraid of science. He also warned against labeling people as fundamentalists.

"They want science that they don't have to be afraid of. They want a science that they recognize that enriches their knowledge of truth, which ultimately brings them closer to God. The only science they've seen on television is as unrepresentative as the only religious people they've seen on television. They need to see people of faith who are scientists, people of science who are faithful," he said.

At the reception following the lecture, St. Paul Church parishioner John Keck said Brother Guy's presentation "had a personal focus."

"A lot of scientists tend to look at science as being like we're looking down on the universe, as opposed to being part of the universe, and religion really brings out that aspect of being part of the universe, being part of his creation," Keck said.

Karin Oberg, a professor of astronomy at Harvard University, who introduced Brother Guy at the first of his two lectures, shared her thoughts in an email to The Pilot.

"I think Brother Guy provides a powerful witness of the possible harmony of science and faith within a person. There are many misconceptions both on what religious people mean by faith and what questions science can address. By addressing these misconceptions, Brother Guy hopefully removes both obstacles to faith for science-minded students, and obstacles to a pursuit of science for people of faith," Oberg said.