'Spirit of Sacrifice and Generosity': St. John's Seminary and the 1918 pandemic

On Aug. 28, 1918, an outbreak of influenza was detected aboard a receiving ship at Boston's Commonwealth Pier. "Unless precautions are taken," wrote Dr. John S. Hitchcock of the Massachusetts Department of Health, "the disease in all probability will spread to the civilian population of the city." Despite the department's swift actions to contain the disease, it spread like wildfire, first through the maritime population and, by mid-September, to civilians.

In an effort to minimize the spread of the disease, state and city officials enacted measures that would be all too familiar to us today. Theaters, movie houses, saloons, and dance halls were closed. Public gatherings were prohibited. Citizens were advised to avoid unnecessary travel on streetcars, subways, and trains. Still, Boston hospitals overflowed with patients, and the situation became more desperate as the city's doctors and nurses themselves became infected with influenza.

At St. John's Seminary in Brighton, administrators moved to delay the start of fall term, originally set to begin on Sept. 26. "Upon the unanimous, unhesitating, and unqualified advice of the four physicians who serve the Seminary," wrote the rector, then-Father John B. Peterson, to Cardinal William O'Connell, "I have announced the postponement of the opening of the Seminary." He informed the cardinal that several students were ill or from families afflicted by influenza. Were the seminary to open, he feared, "the danger of general contagion here would be great."

With the fall term delayed, the clergy who ordinarily served the Seminary dispersed to meet the needs of nearby parishes with sick or vulnerable priests. Tragically, the pandemic would claim the lives of a few of these priests, who contracted influenza as a result of their ministry to sick parishioners. One of these priests was Father Andrew J. O'Brien, professor of dogmatic theology at St. John's Seminary, who died on Oct. 12 after serving at a parish in Hull.

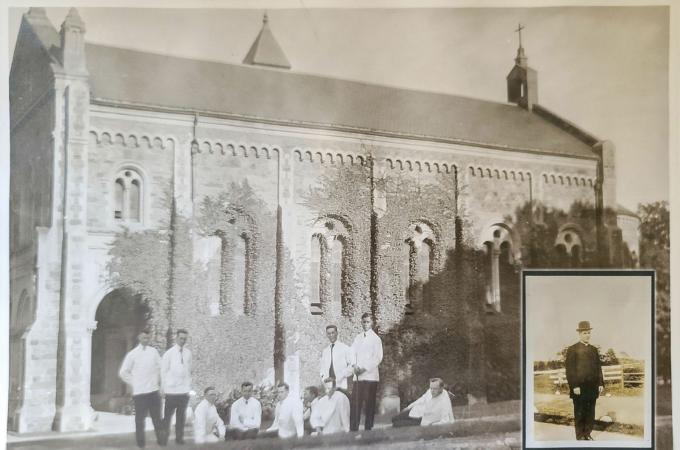

As Boston's hospitals continued to struggle with the volume of influenza cases pouring in each day, Cardinal O'Connell saw an opportunity to put the empty Seminary to good use. In late September, he offered the spacious building and its grounds to the Massachusetts Committee of Public Safety, to be used for the care of convalescents. On Oct. 2, two military officials arrived in Brighton to assess the seminary's suitability for use as a temporary hospital.

After receiving the completed assessment of the seminary, Chairman Henry Endicott of the Emergency Public Health Committee approved its use effective immediately. He wrote to Cardinal O'Connell, "If the place had been built to order it couldn't possibly be better for the purpose ... The splendid building, with its light and airy rooms, large corridors and the fine kitchen facilities are wonderful, and the sunny exposure and the grounds are perfect."

On Oct. 6, St. John's Seminary became St. John's Hospital, as the first 12 patients arrived from Massachusetts General Hospital. Six doctors and nine nurses were appointed to see to the care of these patients and those who would follow. Dr. William H. Devine, head of the medical department of Boston Public Schools, agreed to suspend his private medical practice to oversee the facility.

The doctors and nurses of St. John's Hospital were not to be short-handed; immediately upon the hospital's opening, every one of the St. John's seminarians, who had been instructed to remain at home during the pandemic, volunteered their services to Dr. Devine and his patients. Of their unanimous offer, Henry Endicott wrote, "While it may not be possible to use the entire number, I wish these young men to realize that we are deeply grateful for the admirable spirit of sacrifice and generosity." Twenty seminarians ultimately served alongside the doctors and nurses at St. John's.

In total, 92 patients received care at St. John's Hospital. All were male; the oldest was 77 and the youngest, four. The average stay at the facility was one week. According to Dr. Devine's report on the hospital, "The treatment of convalescents consisted of rest, abundance of good food, fresh air, and ordinary tonic medicines." This regimen appears to have been effective, since the hospital saw no fatalities and all but three patients recovered enough to be discharged home.

In the end, St. John's Hospital was open for only three weeks, between Oct. 6 and Oct. 26. By the end of October, influenza numbers in Boston were dropping precipitously and the city's medical professionals declared to the public that the worst of the pandemic had passed. On Oct. 19, the city revoked all closure orders and allowed businesses to reopen. Children would return to school on Monday, Oct. 21. As the city returned to normal, those few patients still recovering at St. John's were transferred back to traditional hospitals, which now had the capacity to see to their care.

VIOLET HURST IS AN ARCHIVIST FOR THE ARCHDIOCESE OF BOSTON.