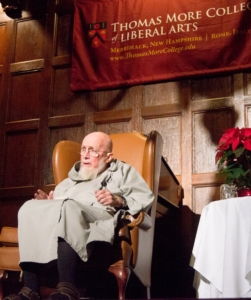

Father Groeschel addresses Thomas More College President's Dinner

BOSTON -- Thomas More College of Liberal Arts welcomed Father Benedict Groeschel and three experts on language and liturgy to speak as part of a day-long event before their annual President's Council Dinner, Dec. 3 at the Harvard Club of Boston in the city's Back Bay.

In the evening, a fellow Franciscan helped Father Groeschel, a founding member of the Franciscan Friars of the Renewal in 1987 and director of the Office for Spiritual Development for the Archdiocese of New York, into a high-backed chair as he took the stage during applause from the crowd in the 500-seat Harvard Hall.

He began the keynote address speaking on the subject of a transition between the social upheaval in the 1960s and 1970s and a movement toward more open governance in the current times, detailing his views on what the Church can expect in the future. His keynote address outlined a sense of optimism for people of faith, despite the complications caused by secularization in the United States.

"The United States has moved, more and more, to a more genuine -- genuine -- democratic society, which is much more tolerant of its different members," Father Groeschel said, opening his talk.

"I can tell you that, any politician who ran for any public office and he identified himself as an anti-religious, as he neared political election, he'd be dead. D-E-A-D dead. The country has a puzzling attitude toward religion, and religion is a very complicated thing in the United States," he continued.

Father Groeschel went on to discuss the current economic troubles, and the Church in the context of the problems facing society in this country and in the rest of the world.

He spoke of small, yet stridently faithful, communities of the faithful living throughout the world.

"In France you have 75 percent of the people that were baptized, technically Catholic, but only about ten percent were actively following Catholicism," he said. "That ten percent is a very devout group."

He identified the United States as a safe haven for the faithful, because in the U.S. no government agency has ever made any serious attempts to tax or collect revenue from religious institutions.

"Nobody has that thought," Groeschel said. "In public life, even in the media, there is real respect for religion."

Throughout the address he repeatedly touched on the role of religion in the public lives of politicians and candidates.

"Certainly, all the major politicians, and even most of the minor ones, will identify themselves as pro-religious," Father Groeschel said.

Speaking with The Pilot after his talk, Father Groeschel identified one aspect of Catholic teaching as a great priority for Catholics. He called the gathered to focus on service and charity to the poor as a Christ-like way of drawing positive attention to the Church and people of faith.

"People would do well, in their own spiritual life, to look around," Father Groeschel said.

"Look around at elderly people, living all alone; look around at poor families, living nearby. You know, everybody thinks they live in suburbia, but on the edges of suburbia live the poor. St. Vincent de Paul said, 'Love the poor, and your life will be filled with sunlight, and you will not be frightened at the hour of death,'" he continued."

Father Groeschel's keynote address capped a day-long symposium, "The Language of Liturgy: Does It Matter?" featuring three speakers discussing aspects of the changes to the new Roman Missal.

Father George Rutler, Russell R. Reno, and Anthony Esolen each addressed the changes in the language of the liturgy from casual, academic, and artistic perspectives.

"Each of these speakers for different reasons has a known excellence with respect to either liturgy, or language, or both of them together," said Thomas More College dean Christopher Blum.

Father George Rutler of the Archdiocese of New York is a documentary film-maker, author and contributor to numerous scholarly and popular journals. He spoke about casual attitudes toward language corroding the previous translation in a culture of cynicism.

He used the Emperor Julian the Apostate, a 3rd century critic of Christianity, as an example of how cynicism impacts not only the religious body of the Church, but also detracts from the coherence of conversation surrounding its work in liturgy.

"Julian today, when asked of matters of religion, probably would have used the current refrain, 'Whatever,'" Father Rutler said.

He said to pursue the truth, particularly the truth of Christ, people must take great care in their use of language. His talk connected articulate, thoughtful language with deep thinking and deepening faith.

"Why are people afraid of raising the bar?" He asked. "Because it raises us closer to God. It takes us out of ourselves."

Russell R. Reno, editor of the journal First Things, discussed the changes to the liturgy from a more academic position, presenting Jesus in the role of teacher and orator.

"The Risen Christ pours out the Holy Spirit, but not hither and yon," the author said. "Instead he pours it out to biblically and liturgically formed followers."

He said the changes in liturgical language move people beyond simple understanding.

"Out of Israel's scriptures, out of the words of the apostles, and in and through the life of the Church, God has forged a language for us," Reno said. "He gives us the words whereby our spiritual imaginations are healed."

Anthony Esolen, author of 12 books, brought his experience as a published commentator on scripture, as an English professor at Providence College, and as a specialist on Renaissance and Middle Age literature to bear, highlighting the artistic role of poetic language in scripture.

"The new translation brings out the poetry that had been simply abandoned," Esolen said.

"I won't say that it had not been rendered well, because that would imply that the translators in 1973 actually tried to render it. They did not," he added.

Esolen presented Jesus Christ as a poet of sorts, using a mustard seed as a metaphor for the Kingdom of God as he enlightened his students. Esolen said, presumably, the students had seen mustard seeds before.

"The parable turns our attention from a familiar term, The Kingdom of God, to a wholly unfamiliar and mysterious being, namely The Kingdom of God, as it really exists," Esolen said. "The soul of poetry is not so much to make strange things familiar, but to make familiar things strange."