Spirituality

Christ willed to make himself a captive from the beginning of his appearance on earth.

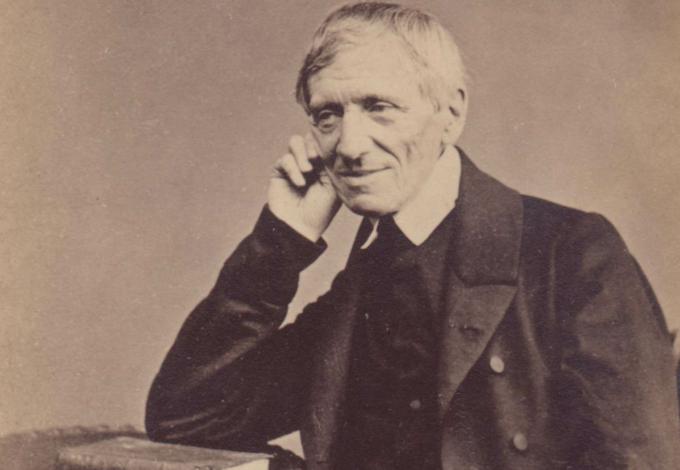

Pakaluk

Finding a volume of John Henry Newman's writings in a second-hand book store used to be like finding gold. But today all of his works are available for free at an attractive website, NewmanReader.org.

Many Catholics know of Newman's sensitive "defense of how he lived his life," or "Apologia Pro Vita Sua," and his defense of a distinctively Catholic and liberal education, "The Idea of a University." But Newman was a pastor before being a writer. As great as these works are, Newman's real masterpieces are his sermons, especially his "Parochial and Plain Sermons," but also his "University Sermons" and "Sermons Preached on Various Occasions." As the last title indicates, Newman's sermons are typically linked to times in the liturgical calendar.

One of the most famous of these, "Omnipotence in Bonds," was preached for the Christmas season. Its first half is a mediation on God's omnipotence. In Newman's Anglican-period sermons, it is clear that he dwells on dogmas such "I believe in God the Father, the Almighty," because he is concerned that his congregation, as well as the Church of England, has drifted away from the Christianity preached by the Apostles and accepted by the first converts. But in "Omnipotence" and other Catholic sermons, his purpose is different, to help Catholics appreciate better the truths which he does not doubt that they profess.

"If you wish to enter into this idea of Omnipotence, and investigate what it is, trace it back into the further mystery of a past eternity. For ages innumerable, for infinite periods, long and long before any creature existed, he was. When there was no creature to exercise his power upon, still he was Omnipotent in his very Essence, as being not sovereign merely, but sole."

Note by the way the music in Newman's language -- how, for instance, "but sole" at the end of one sentence echoes "he was" in the other.

"He can make, he can unmake; he can decree and bring to pass, he can direct, control, and resolve, absolutely according to his will. He could create this vast material world, with all its suns and globes, and its illimitable spaces, in a moment. ... he could destroy it all in all its parts in a moment; in the same one moment he could create another universe instead of it, indefinitely more vast, more beautiful, more marvelous, and indefinitely unlike that universe which he was annihilating."

Newman offers this mediation because he wishes us to realize vividly that God in his nature, as omnipotent, is entirely free and unconstrained. The creature can make no claim on Him. God has no "duties" toward creatures, as Newman says. Thus if God were to bind himself, this would be an entirely free act. Yet such freely willed bondage, Newman argues, is a permanent characteristic of the incarnation -- what Newman refers to as a "law of captivity."

Christ willed to make himself a captive from the beginning of his appearance on earth. He could have come down from heaven a mature man like Adam, but he chose to endure the confinement of his mother's womb, "There was he in his human nature, who, as God, is everywhere; there was he, as regards his human soul, conscious from the first with a full intelligence, and feeling the extreme irksomeness of the prison-house, full of grace as it was."

Then, the moment he is born, Mary wraps him tightly like a mummy in swaddling clothes. Next, he grows up confined to a tiny house in a small village. He is subject to his parents and constrained to learn Joseph's trade. The one time he "gets free" and converses with rabbis in the Temple, his mother and foster father immediately call him back.

He lives confined to that household until he is 30. But the "law of captivity" continues even after he leaves. The moment he is baptized and enters public ministry, Satan gets power over him and drags him around the desert and to a pinnacle. After his ministry begins, his relatives try to constrain him. Crowds try to throw him over a cliff. He is betrayed "into the hands of violent men," chained, imprisoned, and killed. His body is sealed in a tomb.

Even after the resurrection the "law of captivity" holds: "He took bread, and blessed, and made it his body; he took wine, and gave thanks, and made it his blood; and he gave his priests the power to do what he had done. Henceforth, he is in the hands of sinners once more. Frail, ignorant, sinful man, by the sacerdotal power given to him, compels the presence of the Highest; he lays him up in a small tabernacle; he dispenses him to a sinful people. Those who are only just now cleansed from mortal sin, open their lips for him; those who are soon to return to mortal sin, receive him into their breasts; those who are polluted with vanity and selfishness and ambition and pride, presume to make him their guest; the frivolous, the tepid, the worldly-minded, fear not to welcome him. Alas! Alas!"

But why is captivity a "law" of the incarnation, Newman asks? Because "the very principle of sin is insubordination." Thus the child of Bethlehem gives a saving example "in his own person of that love of subjection, which in him alone is simply voluntary, but in all creatures is an elementary duty."

MICHAEL PAKALUK IS CHAIRMAN AND PROFESSOR OF PHILOSOPHY AT AVE MARIA UNIVERSITY.

- Michael Pakaluk is Professor of Ethics and Social Philosophy in the Busch School of Business at The Catholic University of America. His book on the gospel of Mark, ‘‘The Memoirs of St. Peter,’’ is available from Regnery Gateway.

Recent articles in the Spirituality section

-

No line-drawingMichael Pakaluk

-

Physician-assisted suicide is a slippery slopeCardinal Seán P. O’Malley

-

He saw the cloths and believedBishop Robert Barron

-

God's instrument for viewing the crucifixionMichael Pakaluk

-

QuinquagesimaMichael Pakaluk