Culture

As families receive advice about how to care for their loved ones, and try to make good decisions on their behalf, one question that should be asked is, "What is the reason someone is being given (or is being advised to receive) pain medication?"

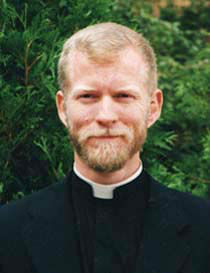

Pacholczyk

To help people navigate some of the complex decisions involved in end-of-life situations, the National Catholic Bioethics Center offers a free and confidential consultation service via e-mail or phone (see www.ncbcenter.org/ask-a-question). Often, we are asked about the appropriate use of morphine and other opioids. Family members may be understandably concerned about the potential for overdosing their loved ones, as hospice workers appear to "ramp up" the morphine rapidly, especially in the last few hours of life.

What principles can guide us in the appropriate use of morphine near the end of life? It can be helpful to summarize a few key points here.

Morphine and other opioids can be very useful -- indeed, invaluable -- in controlling pain and reducing suffering for many patients near the end of life. Morphine is also used to alleviate anxiety and labored breathing. Opioids are highly effective pain management tools in the toolbox of palliative care and hospice specialists.

These drugs need to be used carefully, since very high doses are capable of suppressing a patient's ability to breathe, which can lead to death.

Medically appropriate use of these drugs for pain management will involve the important concept of "titration." Dosage titration means giving enough medication to dull or limit the pain, but not going so far as to cause unconsciousness or death. This implies continually assessing and adjusting the balance of a drug to assure it is effective and not unduly harmful. In other words, pain medications should be dispensed in response to concrete indicators of pain and discomfort, so that patients can have their pain-relief needs met but not be unnecessarily over-medicated.

Practically speaking, it is important to pay attention to signs of discomfort that a patient may be manifesting, whether grimacing, twitching, crying, flailing extremities, or other movements. Such objective indicators should guide those making dosing decisions as they seek to control pain and limit discomfort.

As families receive advice about how to care for their loved ones, and try to make good decisions on their behalf, one question that should be asked is, "What is the reason someone is being given (or is being advised to receive) pain medication?" Is the medication being provided because the patient is actually experiencing pain, or for some other reason, such as an intent to hasten death? This can be an important factor in determining whether the administration of a particular pain medication would be ethical or not.

By carefully dispensing pain medications without rendering patients lethargic or semi-comatose, to the extent possible, we afford them the opportunity to make preparations for their death while still conscious. In general, patients should not be deprived of alertness or consciousness except to mitigate excruciating or otherwise unbearable pain.

In order to address situations of escalating pain, it may become necessary to administer higher and higher doses of morphine or other opioids. At a certain point, we may face the prospect that the next dose we provide to properly control the pain will be so high that it will suppress the patient's breathing, leading to death. The principle of double effect can guide and assist us in such cases. When the clinical requirement of proper titration of pain medications is carried out, and the other conditions of the principle are satisfied, a strict and appropriate use of pain medication in this manner can be allowable, even when it may indirectly or unintentionally contribute to an individual's demise.

This has been helpfully summed up in Directive 61 of the Ethical and Religious Directives of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, which reminds us that, "Medicines capable of alleviating or suppressing pain may be given to a dying person, even if this therapy may indirectly shorten the person's life so long as the intent is not to hasten death. Patients experiencing suffering that cannot be alleviated should be helped to appreciate the Christian understanding of redemptive suffering."

In situations of truly intractable pain, it can be legitimate to employ "palliative sedation," which involves the decision to render a patient unconscious during his or her final hours. This should be done with proper consent, obtained from the patient or the designated surrogate. It is important to avoid any suicidal intention and to ensure that other duties, such as receiving the last sacraments and saying goodbye to loved ones, have been fulfilled.

Such careful attention to pain management is of paramount importance in end-of-life care and supports both the patient and the family in a dignified way during the dying process.

- Father Tadeusz Pacholczyk, Ph.D. earned his doctorate in neuroscience from Yale and did post-doctoral work at Harvard. He is a priest of the diocese of Fall River and serves as the Director of Education at The National Catholic Bioethics Center in Philadelphia,

Recent articles in the Culture & Events section

-

Scripture Reflection for April 14, 2024, Third Sunday of EasterDeacon Greg Kandra

-

St. Helena's House is established in the South EndThomas Lester

-

Is this synodality?Russell Shaw

-

Poking the hornet's nest of IVFFather Tadeusz Pacholczyk

-

A eucharistic word: MissionMichael R. Heinlein