Spirituality

If you were to say that assisted suicide is permissible when a sufferer is in screaming pain and within days of his death, what prevents you from saying that it should be permitted when he is within weeks or months of his death, or when his pain is more psychological than physical, or when the state decides it is expedient?

Barron

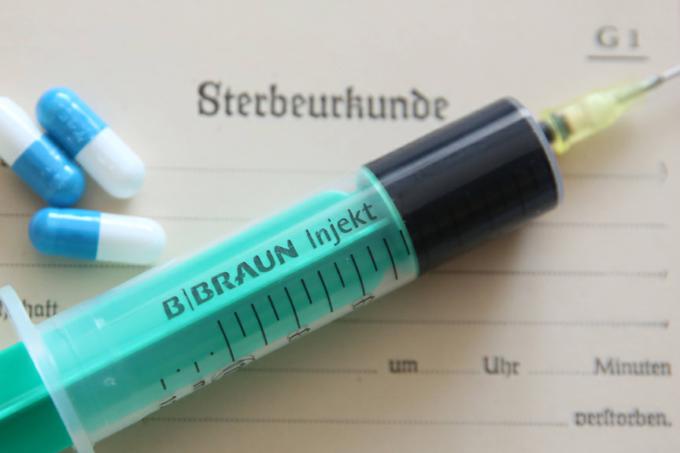

Speaking last week at a conference in Italy, Archbishop Vincenzo Paglia, president of the Pontifical Academy for Life and grand chancellor of the John Paul II Pontifical Theological Institute for Marriage and Family Sciences, seemed to suggest that, under certain circumstances, the assisted suicide of the infirm would be morally acceptable. These are his words: "Personally, I would not practice suicide assistance, but I understand that legal mediation may be the greatest good concretely possible under the conditions we find ourselves in." There was a powerful reaction to this statement on the part of many concerned Catholics, and in the wake of the controversy, the Archbishop clarified that he was not addressing the moral dimension of the problem, only its legal ramifications. Now, I don't wish to engage in a parsing of the Archbishop's words, still less in an exploration of his motives, but I do indeed want to explore why so many were so upset. It has to do with the moral theory called "proportionalism," which was all the vogue when I was going through university and seminary studies years ago.

According to the proportionalist theorists, there are no moral acts that are intrinsically good or evil, only acts that have both positive and negative consequences. Accordingly, the way that one should gauge the goodness or wickedness of a given act is rationally to assess its effects and determine whether the positive outweighs the negative. If there is a preponderance (a proportion) of the former over the latter, the act under consideration can be considered morally praiseworthy. It should be clear that proportionalism so defined is a close cousin of the moral theory called consequentialism. So, when contemplating whether an abortion could be justified, the proportionalist would assess the various and complex outcomes of the act. On the one hand, we have the death of the child and the inevitable sadness of all concerned, etc.; and on the other hand, we have, say, an improvement in the overall mental health of the mother, an amelioration of the family's economic situation, greater career opportunities for the mother, etc. If, in the judgment of the moral reasoner, the good consequences outweigh the bad, the abortion can be permitted.

I'm sure you can see that, once the category of the intrinsically evil is set aside, practically anything can be justified on proportionalist grounds. In classical moral theory, intrinsically evil acts would include, among many others, the direct killing of the innocent, the enslavement of other people, torture, and sexual intercourse with children. No matter what positive consequences could possibly follow from these, they could never be justified, since they are, in themselves, morally repugnant. But on strictly proportionalist grounds, one could vindicate slavery, as many did as late as the 19th century in our country, because of its presumably good economic and cultural effects. One could similarly legitimize the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which killed upward of one hundred thousand innocents, but which, arguably, saved the lives of countless more. One could give plausible reasons for torture, provided it rendered militarily useful information. And one might even make excuses for having sex with children: after all, the ancient Greeks thought it was an indispensable part of the education of boys. Or to return to the case suggested by Archbishop Paglia, assisted suicide might be regrettable and yet permissible, on the condition that it put an end to the terrible suffering of a terminally ill patient.

Mind you, there is no reason to call into question the personal integrity of the proponents of proportionalism. They undoubtedly feel that they are exercising both common sense and compassion in the formulation of their theory. But the doctrine remains dangerous indeed. And it was precisely to refute it that Pope St. John Paul II composed what I consider the greatest of his encyclicals, "Veritatis Splendor." In a way, that entire letter is a sustained argument against proportionalism, but the following section of section 80 is a good summation:

Reason attests that there are objects of the human act which are by their nature 'incapable of being ordered' to God, because they radically contradict the good of the person made in his image. These are the acts which, in the Church's moral tradition, have been termed 'intrinsically evil' (intrinsece malum): they are such always and per se, in other words, on account of their very object, and quite apart from the ulterior intentions of the one acting and the circumstances. Consequently, without in the least denying the influence on morality exercised by circumstances and especially by intentions, the Church teaches that 'there exist acts which per se and in themselves, independently of circumstances, are always seriously wrong by reason of their object.'

I studied proportionalism when I was a young man, and I certainly felt its attractiveness. It does seem to be a sensible form of moral reasoning, indeed the default position of most people. When assessing an act, I daresay, the majority of human beings instinctually reach for some version of it. But John Paul II gave voice to the Church's long-held conviction that proportionalism, consistently applied, opens the door to moral chaos. If you were to say that assisted suicide is permissible when a sufferer is in screaming pain and within days of his death, what prevents you from saying that it should be permitted when he is within weeks or months of his death, or when his pain is more psychological than physical, or when the state decides it is expedient? To deny the category of the intrinsically evil is to place oneself, inevitably, on a slippery slope to complete moral relativism.

From St. Paul of Tarsus (see Rom. 3:8) to St. John Paul II, the Church has stood athwart such subjectivism. May it continue to do so.

- Bishop Robert Barron is the founder of the global ministry, Word on Fire, and is Bishop of the Diocese of Winona-Rochester.

Recent articles in the Spirituality section

-

Pushed off the platformMichael Pakaluk

-

Advice to fathersMichael Pakaluk

-

The higher you go liturgically, the lower you should go in service of the poorBishop Robert Barron

-

The Easter Season is the fleshly seasonMichael Pakaluk

-

Ripley and RupnikEffie Caldarola