Reports of 1848 unrest in France

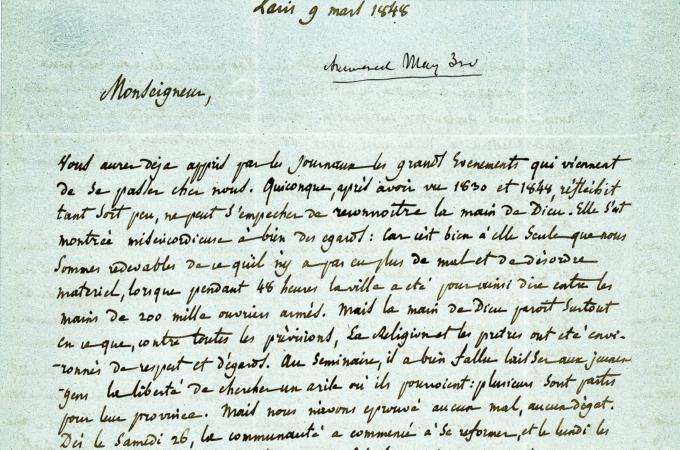

On March 9, 1848, Abbe Carriere of the Seminary of Saint-Sulpice, Paris, wrote Bishop John B. Fitzpatrick of Boston about the events which had transpired in Paris the previous month.

The Society of Saint-Sulpice was established in Paris in 1642, with the mission "to prepare young men in seminaries for ecclesiastical life, and for Holy Orders, by training them in the knowledge and virtues required by the dignity of the Priesthood and Sacred Ministry." They were teaching students as early as December 1641, but the seminary moved to the parish of Saint-Sulpice the following year, giving the society its name. In the 18th and 19th Century they would establish a college and seminary in Canada, where aspiring priests from New England were sent to study, with the most promising continuing their education at the seminary in Paris. Early students from Boston included Bishop Fitzpatrick himself, and later Archbishop John J. Williams. When the latter founded St. John's Seminary in Brighton, he invited the Sulpicians to staff the seminary until Cardinal O'Connell replaced them with diocesan priests in 1911.

In his letter, the Abbe refers to the Revolutions of 1848, a series of uprisings across Europe that year. Affected countries included Italy, France, Prussia, and the Austrian Empire, among others, each instance often treated as separate events with their own causes. In most cases, whatever the cause, there was generally some element of people calling to reform the structure of each nation's government, many still monarchical in nature. These desired reforms are seen as a movement towards the formation of single nation states -- for example, the eventual unification of Italy in 1871 -- though in 1848 that was not an immediate outcome.

In France, uprisings in February saw the removal of King Louis Phillipe, and a new government of elected officials formed, known as the Second Republic. The Abbe, in his letter, writes of his relief that there is no more disorder and that, by the Hand of God, the priests were left unharmed at the seminary. The seminarians, on the other hand, were allowed to leave for the safety of the countryside, but by Sunday the 26th had returned, and classes commenced the following day. Of the seminarians from Boston, he writes, they showed courage and calmness throughout the events that had transpired. He was very grateful that Paris was now tranquil, and reiterates that it is on God alone that he can depend to keep them safe during these trying times.

By June of that year, infighting amongst elements of the new government would see a resurgence, and Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, Napoleon I's nephew, elected as the new president. In 1851 he would organize a coup d'etat and on Dec. 2, 1852, took his place as Emperor Napoleon III.

- Thomas Lester is the archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston.