The paradoxes of inclusion

In a recent homily, Bishop Robert E. Barron rightly identified two paramount values in our secular culture: being "inclusive" and being "nonjudgmental."

The two seem closely related. If you want to embrace everyone in society, you avoid making moral judgments that banish some people to the margins. So all are welcome, along with their own moral views -- unless they commit the sin of being judgmental.

Big problems emerge when a society tries to act on this idea.

Take the federal law forbidding sex discrimination, commonly called Title IX. Congress enacted it to end exclusivism at schools and colleges, where women could not take part in athletic events or win institutional support for their sports teams. The law has worked well.

But in the name of inclusion, the Obama administration reinterpreted it to protect those who identify themselves as belonging to a gender they were not born with.

The result? Men who identified as women could win all women's tournaments that rely on upper body strength. In theory, a college could legally have two wrestling teams -- one made up of men, and one made up of men who identify as women. And the law's purpose, equal inclusion of women in sports, is destroyed. Federal courts ended up rejecting the Obama proposal as contrary to Congress' intent.

Inclusion also quickly becomes its opposite when it enforces its ban on "judgmentalism." In their zeal to include same-sex relationships under the banner of marriage, for example, some have launched legal attacks against Christian bakers, florists and others trying to live by their Christian beliefs on marriage. Driving people from their livelihood based on their religion is an obvious example of exclusion.

Or take the public campaign against the fast-food chain Chick-fil-A because it is opening outlets in New York City. The chain's owners believe in the historic Christian view of marriage. Gay rights advocates oppose this "infiltration" of New York, in line with the sentiment Gov. Andrew Cuomo expressed last year: "As a New Yorker, I am a Muslim. I am a Jew. I am black. I am gay. I am a woman seeking to control her body. We are one New York."

But pro-life citizens, faithful Catholics and other traditional Christians -- not to mention people who enjoy delicious chicken sandwiches -- may not be welcome in this New York.

These campaigns have been launched against people seeking simply to live their own lives by their beliefs. The Christian baker whose case is now before the Supreme Court, as well as the owners of Chick-fil-A, serve all customers equally. They believe in the equal dignity of all people, but not the equal moral status of all actions and relationships. So the baker cannot in conscience make a wedding cake for something his faith says is not a wedding.

If secular Americans want to include everyone, they will need to welcome even people with Christian convictions. That doesn't mean endorsing those convictions. Perhaps, like Christians, they could learn to "hate the sin but love (or at least not exclude) the sinner."

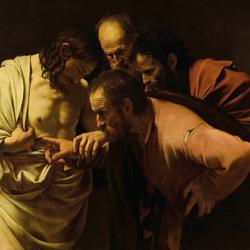

We Christians are called to something more demanding. We hate the sin because we love the sinner, because sin hurts those who practice it. We are called to embrace every human being made in the image and likeness of God, and pray for all people to attain their full God-given potential. That means humbly making judgments about behavior that can block this from happening.

If others see that as judgmental, and therefore a sin, they might ask themselves how they can be judgmental against those who believe in the reality of sin and grace.

- Richard Doerflinger worked for 36 years in the Secretariat of Pro-Life Activities of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. He writes from Washington state.