Nation

The story behind an anti-Nazi priest and a Florida miracle

By Kevin Jones

Posted: 1/10/2018

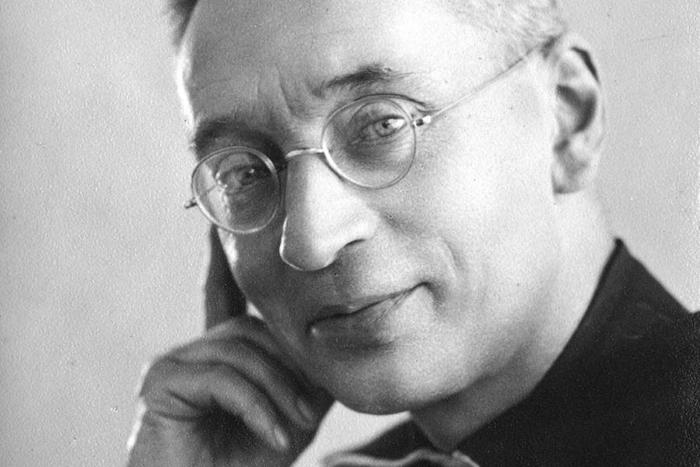

Blessed Titus Brandsma OCarm Public Domain CNA

Palm Beach, Fla., Jan 9, 2018 CNA/EWTN News.- More people need to know about the Dutch priest Blessed Titus Brandsma and his heroic death in a Nazi concentration camp, according to a Florida priest who says Brandsma’s intercession led to a miraculous healing from cancer.

“He was bold. He was brave,” Father Michael Driscoll, 76, told CNA. “He knew when he was in the pulpit preaching that there were people in the congregations taking notes for the Nazis about what he would be saying. Yet he continued.”

Driscoll has faced his own struggles. He was diagnosed with advanced melanoma in 2004. Shortly after that, someone gave him a small piece of Brandsma’s black suit, which the American priest applied to his head each day.

He underwent major surgery, with doctors removing 84 lymph nodes and a salivary gland. He then went through 35 days of radiation treatment, the Boca Raton Sun-Sentinel reports.

Still, his cancer had a very poor survival rate, of only 10 to 15 percent after ten years.

“Doctors have stated Fr. Driscoll’s cancer is now gone and have said his good health over the past 12 years defies all odds,” the Diocese of Palm Beach said Dec. 13. “They have stated his healing and recovery from Stage 4 cancer cannot be explained medically."

Driscoll recounted his doctor’s words three and a half years ago: “no need to come back, don’t waste your money on airfare in coming back here. You’re cured. I don’t find any more cancer in you.”

The apparent miracle could lead to the canonization of Bl. Titus Brandsma. The Palm Beach diocese, where Driscoll serves as a retired priest, sent its findings and evidence to the Vatican in December 2017.

Brandsma, a Netherlands-born Carmelite priest, was a professor and a journalist. He was a strong critic of Nazi ideology. After the Nazis occupied his country in May 1940, they persecuted Jewish citizens and laid increasing restrictions on others.

The priest defended freedom of Catholic education and of the Catholic press against Nazi pressures.

“He was a spokesperson for the Dutch bishops,” Driscoll said. “He got the message across against the Nazis and what they were doing against the Catholic press, the Catholic schools, the persecution of Jews, you name it.”

Due in part to Brandsma’s refusal to expel Jewish children from Catholic schools and because he opposed mandatory Nazi propaganda in Catholic newspapers, he was arrested by the Nazis in January 1942. He was was eventually sent to the Dachau concentration camp in Germany, joining 2,700 other clergy. He faced inhumane conditions and abuse from his captors.

“He apparently was very kind to other prisoners, telling them to forgive the people who were persecuting them and punishing them in this prison, giving up little bits of his food to others,” Driscoll recounted.

Non-German priests weren’t allowed to celebrate Mass in the camp, where the majority of the priests were Polish.

Still, Brandsma carried out priestly duties.

“The German priests used to smuggle the Eucharist to him so he could distribute it to various prisoners, by an eyeglass case. That’s where he hid the Eucharist,” said Driscoll. “He would go around giving encouragement to other prisoners and giving them the Eucharist too, as best he could.”

Brandsma, who was always frail, was sent to the prison hospital.

“It is said that anybody who went to this prison hospital never came out,” Driscoll said. “Probably when he went there, he knew all sorts of things might happen to him.

The hospital’s doctors regularly engaged in human experimentation.

Driscoll said a nurse gave Brandsma a lethal injection on July 26, 1942 and he died immediately. His remains were likely cremated within a day. He was 61 years old.

A nurse on duty at the time of the priest’s death later testified that the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police, had ordered his death.

“Before he died, he gave this person his rosary, which was a rather primitive rosary, made with some kind of beads,” Driscoll said. “He told her to pray the rosary. She objected that she didn’t understand how and wasn’t a believer anymore.”

“He said all you have to do is go from bead to bead and say ‘pray for us sinners, now and at the hour of our death, Amen.’ And just keep saying ‘pray for us sinners, pray for us sinners’. And that’s enough,” the American priest recounted.

Brandsma was beatified in November 1985 as a martyr for the faith.

For Driscoll, the priest’s life teaches us “to preach the gospel boldly, forcefully, and not be afraid.”

“I think that’s one of the important issues,” he said. “Being kind to one another, as he was to his fellow prisoners, and try to console them when they fell down. I assume many of them were totally depressed by their condition. He encouraged people.

Driscoll also reflected on the nature of faith, sickness and healing. Those who suffer illness should “try their best… try to not lose hope.”

“It’s faith that heals. I believe, and that’s important,” he said. “I tell people ‘It’s not the touching of this piece of cloth to you. It’s faith that saves.’ You should not give up hope, but have faith. Jesus says ‘ask and you shall receive.’ You keep praying for that. Certainly everybody’s prayer is answered somehow. It may not be the way that you like, but it is answered.”

Fr. Mario Esposito, a Carmelite priest from New York, is a vice-postulator for the case. He told the Sun-Sentinel that he knows of no other miracles attributed to Brandsma that are under investigation.

“We hope this could be the one, but there are very exacting standards, and Rome is going to go over this case with a fine-toothed comb,” Esposito said.