Faith

"The true 20th-century liturgical movement, however, is widely considered to have begun with a Belgian Benedictine, Lambert Beauduin . . ."

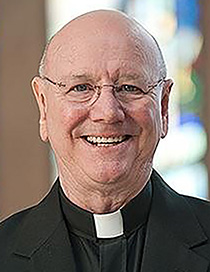

SJ

Dec. 4, 2023, marks the 60th anniversary of the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy of the Second Vatican Council. "Sacrosanctum Concilium" -- documents of the Holy See are usually referred to by their first two or three words in Latin -- was approved by the bishops by a vote of 2147-4. Ironically, the final vote came on the morning of Nov. 22, 1963. Obviously, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy later that day in Dallas overshadowed what was to become one of the landmarks in the modern history of Catholicism.

The constitution was the fruit of several centuries of scholarship and pastoral experience. Although the liturgy of the Roman Rite remained relatively stable in the centuries following the Council of Trent (1545-1563), a massive amount of historical and textual scholarship revealed that the desire of Pope St. Pius V to restore "the Missal itself to the original form and rite of the Holy Fathers" was greatly impeded by a lack of historical sources. Beginning in the 17th century with the rise of modern historical studies by some perhaps little-known scholars, like French Benedictines Edmond Martene and Jean Mabillon and the Italian diocesan priest Ludovico Muratori, scholarship found greater access to the liturgical materials of the early church. These historical studies, as well as the philosophical concerns of the Enlightenment, led to the decrees of the Synod of Pistoia (Tuscany) in 1786 under Bishop Scipione de' Ricci. In liturgical terms, this synod decreed a major streamlining and modernization of the liturgy, for example, by decreeing that there be only one altar in a church as well as limiting statues and processions. Although its decrees were swiftly suppressed by Pope Pius VI (1794), much of Pistoia's agenda survived in the liturgy constitution. As a matter of fact, some of the post-Vatican II criticism of the constitution, and of the liturgical reform in general, focused on the fact that some of what was condemned by Pope Pius VI was now approved.

The 20th-century liturgical movement that helped produce Sacrosanctum Concilium had diverse starting points. One major step in the century before Vatican II was the establishment of the Benedictine Monastery of Solesmes in France by Prosper Gueranger in 1833. Gueranger was determined to restore Gregorian chant as well as to remove neo-Gallican (i.e. contemporary French) elements from the Roman Rite. Shortly after his election to the papacy, Pope St. Pius X issued a motu proprio entitled "Tra le sollecitudini" ("Among the concerns", 1903) calling for the restoration of Gregorian chant. It was this document that provided inspiration for the memorable phrase about active participation in the liturgy as the indispensable font of the Christian life that found its way into the constitution (SC #14).

The true 20th-century liturgical movement, however, is widely considered to have begun with a Belgian Benedictine, Lambert Beauduin, who founded the Abbeys of Mont-Cesar and Chevetogne, both in Belgium, and encouraged more popular liturgical knowledge and participation by means of educating the laity with regard to the nature and meaning of worship. A number of other pioneers followed, among them Romano Guardini; Pius Parsch, OSA; Odo Casel, OSB; and, here in the U.S., Virgil Michel, OSB of St. John Abbey in Collegeville, Minn.

On an official level, at the end of World War II, Pope Pius XII issued an encyclical on the liturgy, entitled "Mediator Dei" (1947), which gave a blessing, albeit a rather cautious one, to the liturgical movement and inspired and prompted the establishment (1948) of a papal commission for the reform of the liturgy.

Although many of the liturgical reforms inspired by Vatican II seem quite bold, it should not be forgotten that the 1950s saw some very significant reforms, including the reform of the Holy Saturday vigil (1953) and the rest of the Holy Week liturgies (1956). Some might recall that prior to 1953 the Easter Vigil was celebrated on Holy Saturday morning with few of the faithful in attendance. It now became a true vigil that concluded with the first Mass of Easter. Other reforms of the Holy Week liturgies included the addition of the washing of the feet to the Holy Thursday Mass of the Lord's Supper and the distribution of Communion to the faithful on Good Friday.

In 1957, Pope Pius XII shortened the fast from all food and drink required before receiving Holy Communion from midnight to three hours for food and one hour for water. Eventually, Pope St. Paul VI further abbreviated the fast to one hour. The change in the fasting discipline eventually led to the permission for evening Masses. These reforms were a foretaste of the reforms subsequently undertaken by the Council.

- Father John F. Baldovin, SJ, is professor of Historical and Liturgical Theology at Boston College School of Theology and Ministry.

Recent articles in the Faith & Family section

-

Did you know?Father Robert M. O'Grady

-

Sowing the Seeds of FaithMaureen Crowley Heil

-

Bread left overScott Hahn

-

Scripture Reflection for July 28, 2024, Seventeenth Sunday in Ordinary TimeJem Sullivan

-

What the universal call to holiness entailsDr. R. Jared Staudt