Culture

. . . He speaks about power, and specifically God's ability to be patient and show restraint in the use of his divine power, and how that is the example by which nations should conduct themselves . . .

Lester

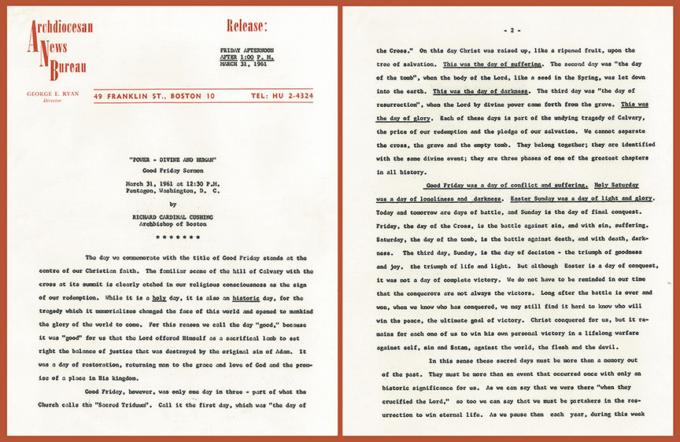

On March 31, 1961, Cardinal Richard J. Cushing of Boston delivered the Good Friday Sermon titled "Power -- Divine and Human" at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., the text of which was released to the public by the Archdiocesan News Bureau that same afternoon. In the sermon, he speaks of Good Friday not in isolation, but as part of the Holy Triduum, and the progression over three days from tragedy to triumph.

Then, as the title implies, he speaks about power, and specifically God's ability to be patient and show restraint in the use of his divine power, and how that is the example by which nations should conduct themselves when exercising their own form of power. In the context of the Cold War in which this was delivered, he specifically alludes to the use of arms, and we can surmise nuclear arms.

Cardinal Cushing's sermon calls listeners to join him at the "familiar scene of the hill of Calvary with the cross at its summit," both a holy and historic day that changed the course of the world. While Jesus' crucifixion is a tragedy, he states. We refer to it as "'good', because it was 'good' for us that the Lord offered Himself as a sacrificial lamb . . . Returning man to the grace and love of God and the promise of a place in His kingdom."

He notes that this event did not occur in isolation and marks the first day of the Triduum. It is a day of suffering, followed by a day of darkness, only to be concluded with a day of glory -- Easter Sunday.

Continuing, he exhorts that the first of these two days are days of battle, and Sunday the day of final conquest, the triumph of life and light. But, he warns, while "Easter is a day of conquest, it is not a complete victory." He explains, "Christ conquered for us, but it remains for each one of us to win his own personal victory in a lifelong warfare against self, sin, and Satan, against the world, the flesh, and the devil."

In that vein, he calls upon Catholics to not view these events in the past tense, as historical events that we memorialize and forget until the next year, but urges that we partake in the resurrection and pause at this time each year not for the purpose of being nostalgic, but to look at our own present battles against sin and how we may overcome temptation to earn eternal life.

Jesus' crucifixion, Cardinal Cushing continues, "is expected to incite in us a return of love for God and for one another" and, furthermore, provide us with an example of obedience, humility, selflessness, patience, and resignation, which we must strive to emulate.

Cardinal Cushing then draws in his audience, bringing them from Calvary to the present, remarking that "undoubtedly, the central fact of man's thoughts and worries at this moment in human history is 'the problem of power.'"

God's divine and limitless power could have prevented Jesus' death at any moment, but he showed restraint and waited to use his power for the purpose of raising Christ from the tomb. "What the Lord was demonstrating on Calvary were those heroic virtues which restrain power and put it to its most effective use. Meekly and humbly, He suffered the abuse of his enemies until he might rise gloriously, and confute their blindness and their infamy."

He then asks, "does not this have a lesson for us in a world full of armaments, a lesson for those who place all their confidence in power?" In conflicts between nations, he continues, we must measure quality as well as quantity; the wise can overcome the strong, the clever the mighty, and ideas can overcome bullets. "And so there are forces greater than the mere physical force of arms and these can bring to destruction those who rely on naked power alone!"

The power that restrains force is virtue, he argues, channeled through moral values. A nation needs fortitude with force and prudence with arms. A strong nation is not a violent one, but a reasonable one, and its strength is derived from the moral fortitude of its citizens. In summation, "that people is strong which conquers itself before conquering others."

A timid nation, he concludes, will fail to defend its rights, or linger in indecision, and will disappear. A rash nation squanders its energies on risks and will pay a price in the long term. The nation with moral fortitude will have balance and will wait in confidence.

- Thomas Lester is the archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston.

Recent articles in the Culture & Events section

-

The example of the Good ShepherdMichael Reardon

-

Spring Celebration Gala will honor Cardinal O'MalleyShannon Lyons

-

Scripture Reflection for April 28, 2024, Fifth Sunday of EasterDeacon Greg Kandra

-

Boston and the nation respond to the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906Thomas Lester

-

See you in the storyLaura Kelly Fanucci