Year of the Eucharist lecture explores modern changes to Mass

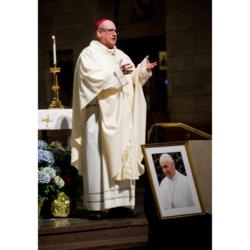

SOUTH END -- The Cathedral of the Holy Cross hosted author and theologian Father Peter Stravinskas on June 6, the Solemnity of Corpus Christi, to share some information and insights regarding the celebration of the Eucharist.

Father Stravinskas preached at the cathedral's four-weekend Masses, led a Vespers service with Eucharistic adoration, and delivered a lecture on the history of Eucharistic liturgy. His June 6 talk was the first in a series of four lectures being held as part of the archdiocese's Year of the Eucharist observances.

During his lecture, Father Stravinskas addressed the problem that inspired the Year of the Eucharist: too many Catholics do not understand or believe the Church's teaching about the Real Presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament and Precious Blood.

"It is not enough to teach the truths of the faith; they have to be reinforced by the signs and symbols of the sacred liturgy. And that's particularly true for a religion like Catholicism which is, to a very high degree, what we call an incarnational religion, that is, a community that takes signs and symbols seriously," Father Stravinskas said.

He shared what he called his "baker's dozen" of changes in the celebration of the Eucharist over the last half a century. He noted that some were made by legitimate authorities, but others were at least initially unauthorized.

The first change concerned how often the faithful received Holy Communion. Pope St. Pius X encouraged more frequent reception in an effort to counter the Jansenist heresy, which discouraged reception because of one's unworthiness to approach the Blessed Sacrament.

"Of course, this was a great good. The problem was that, with the passage of time, it became unthinkable for a Catholic to go to Mass and not receive Holy Communion. The pendulum had swung in the opposite direction," Father Stravinskas said.

Another change was "the near-total eclipse of Latin," which he said, "has had a most deleterious effect on our worship life." He pointed out that the use of a sacral language is common in the history of religions -- for example, Hebrew in Judaism and Arabic in Islam.

The reason for this, he said, is that "the words with which we pray create an atmosphere set apart from our day-to-day existence," and having a language set apart "helps us focus on the uniqueness of our worship."

Requirements for fasting before Communion also changed over the years. The eucharistic fast used to begin at midnight, and included even water, "which was rather onerous and made reception of Holy Communion extremely rare." In 1957, Pope Pius XII modified it to three hours from solid food and one hour for liquids, excluding water and medicine. Seven years later, Pope Paul VI changed it to one hour for solid food or liquids.

"The underlying purpose of the Communion fast is that one's abstinence from normal food would make us yearn more ardently for the supernatural food of the Eucharist," Father Stravinskas said.

In the late 1960s, there was a push for reception of Communion while standing, which became almost a necessity when altar rails were removed.

"The image of communicants lining up as in a supermarket doesn't convey the sacrality of the ritual; on the contrary, it bespeaks something that is very pedestrian," Father Stravinskas said.

Soon after Vatican II, some countries, such as Holland, Belgium, and Germany, began to violate the liturgical law of the time by distributing Holy Communion directly into recipients' hands. Pope Paul VI surveyed the bishops of the world about their attitude toward this practice, and the response was "almost uniformly negative," Father Stravinskas said. To avoid a potential schism, the pope allowed those countries to continue the practice, while forbidding its introduction elsewhere. But other countries tried it anyway, and it was approved by the American bishops in 1977.

This change was soon followed by the distribution of Holy Communion by the non-ordained, as outlined in the document "Immensae Caritatis."

"The document is very clear that recourse to non-ordained ministers of Holy Communion is to be truly exceptional, hence their being called 'extraordinary ministers of Holy Communion,'" Father Stravinskas said.

Contrary to this, he noted, almost every parish in the United States now has such ministers.

Father Stravinskas criticized the applause and "joking around" that sometimes take place during Mass. He also said the way that the sign of peace is made is sometimes a "source of disruption and secularization," turning people's attention to each other instead of the approaching reception of Communion.

"If we believed ourselves to be at the sacramental re-presentation of Calvary, would we think it appropriate to joke?" he said.

Other problematic changes Father Stravinskas noted are the use of "inexact and even heretical language" to describe the Eucharist, the decline in reception of the Sacrament of Penance in order to worthily receive Communion, and changing the placement of the tabernacle from a prominent central location to somewhere out of sight.

Father Stravinskas emphasized that none of the changes he listed were mentioned, let alone mandated, by the Second Vatican Council.

"Regardless of their origin, one cannot gainsay the influence they have had on the spiritual life of the average Catholic," he said.

Looking back on the 56 years since Vatican II, he said, "An honest judgment would have to conclude there has been a massive loss of the sense of the sacred. The 'mystery' has been drained out of our rites, and rites without mystery fall apart, as any sociologist or philosopher of religion would tell you."

Father Stravinskas said he hopes that the Year of the Eucharist will inspire self-examination at the personal, parochial, and diocesan levels.

"If you can take away but one point from my presentation today, make it this: Clear, unambiguous, orthodox teaching on the Holy Eucharist must be bolstered by unequivocal signs and symbols in the sacred liturgy: 'lex orandi, lex credendi,'" he said. That principle, Latin for "the law of what is prayed, the law of what is believed," refers to the integral relationship between prayer and belief, liturgy, and theology.

"That means massive doses of the sense of the sacred, the sense of mystery, the sense of awe in God's presence are all desperately needed," he said.

Richard Clark, the archdiocesan music director, led the music for the vespers service and stayed to hear the lecture afterward.

He appreciated that Father Stravinskas mentioned the 2020 USCCB document, "Catholic Hymnody at the Service of the Church: An Aid for Evaluating Hymn Lyrics," which offers direction about the role of Catholic doctrine in sacred music.

"It puts forth a powerful pastoral opportunity for catechesis, especially with regard to the Eucharist," Clark said.

He said Father Stravinskas "underscored the salutary effects of approaching the Real Presence with greater dignity, reverence, and awe."

There will be three more lectures in the Year of the Eucharist series, addressing the Eucharist in Music on Sept. 12, the Eucharist in Art on Dec. 5, and the Eucharist in Literature on March 6, 2022.