Biography asks whether prestige, Catholic identity are at odds

"American Priest: The Ambitious Life and Conflicted Legacy of Notre Dame's Father Ted Hesburgh" by Wilson D. Miscamble, CSC. Image Books (New York, 2019). 442 pp., $28.

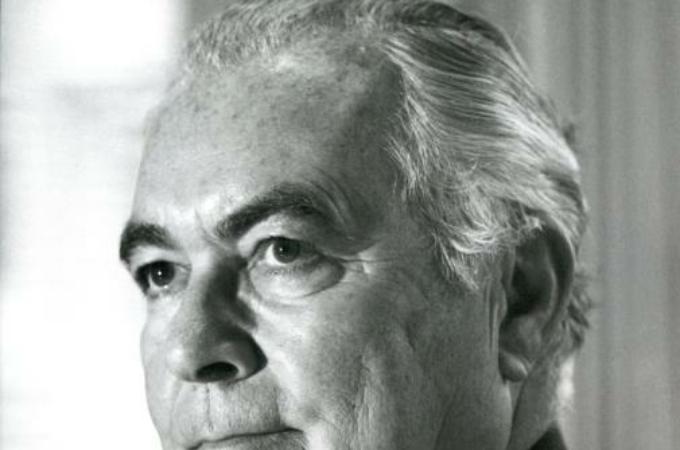

On March 3, 2015, college students donned heavy coats against the brutal Lake Michigan winter and lined a concrete drive on the campus of the University of Notre Dame. In a very particular sense, many of them would not have been there without the efforts of the man to whom they paid their respects -- Holy Cross Father Theodore Hesburgh, who guided that university for 35 years on a path toward ever-higher academic prowess and prestige, but, as a new biography argues, not without tradeoffs.

"American Priest: The Ambitious Life and Conflicted Legacy of Notre Dame's Father Ted Hesburgh" tips its hand with the subtitle. At his passing, the nationally recognized priest was heaped with a mosaic of praise, verging on hagiography, and this book aims to complicate that picture.

There are few biographers more well-equipped for the task at hand than Father Wilson Miscamble, a history professor at Notre Dame who, like Father Hesburgh, is a priest of the Congregation of Holy Cross. Father Hesburgh's presence in seemingly every controversy of mid-century world affairs and domestic politics requires a historian's recall, while the author's personal familiarity with the players in the world of university administration keep the sections covering drama in South Bend from dragging too much.

Father Miscamble also is a veteran of on-campus disputes, notably serving as a faculty adviser to a student-led movement protesting the 2009 honorary degree given to then-President Barack Obama. Father Miscamble is intimately familiar with the litany of complaints leveled at the Hesburgh era by Catholics of a more conservative bent, with the landmark Land O'Lakes statement -- declaring the university's independence from clerical authority -- standing first and foremost.

Yet "American Priest" is not the work of someone with an axe to grind; rather, the book charges the reader to not sand off distinctive Catholic edges in the pursuit of secular recognition, while recognizing the tremendous distinction Father Hesburgh merited for the university he loved so well.

It's hard to imagine any university president today making the cover of Time magazine, for example, as Father Hesburgh did in 1962, much less having the ear of numerous popes and presidents, foundations and philanthropies, donors, faculty, and students -- all while boosting Notre Dame's reputation in the academic establishment.

The sprawling book offers a picture of a life lived to its fullest, while suggesting that Father Hesburgh's pursuit of secular honors undermined the university's Catholic identity. Moving away from an integrated curriculum was just the first step, Father Miscamble argues, in a chain that ultimately saw Father Hesburgh give up on "working for a distinctive institution ... settl(ing) for making his university more modern and more American."

Father Miscamble fairly dings Father Hesburgh for using his renown to advocate for causes that were favorites of the cognoscenti, like nuclear disarmament, while strategically shying away from (though never disavowing) less-popular causes such as the pro-life movement.

At the same time, other 1970s excesses were reined in, sometimes aggressively -- a priest using pizza and Coca Cola as the sacred elements of the Mass was warned by Father Hesburgh (who in all his travel to more than 140 countries never missed saying Mass daily) to desist or be dispatched so fast "his teeth would rattle."

Father Hesburgh's long curriculum vitae defies summary, but a few anecdotes stand out, such as showing then-Vice President Richard Nixon a confessional in Notre Dame's Sacred Heart Church, his skillful handling of Notre Dame football legends from Frank Leahy to Lou Holtz, his "15-minute rule" defusing Vietnam-era student protests, even his post-retirement ride in an SR-71 Blackbird.

But the broad arc of the book is to put Father Hesburgh's vision for Catholic education, and for Notre Dame specifically, in the dock.

For today, the academic caliber of the university has never been higher, the research dollars continue to pour in, and many of the students who lined the path of that frigid funeral procession were likely the same kind of upwardly aspirational strivers who would have otherwise filled the halls of other "peer institutions" without Notre Dame's continuing upward trajectory.

But some of those mourners -- and the professors that teach them -- likely chose Notre Dame over other institutions of higher education not as one option among many, but in their search of a rigorous and distinctively Catholic ethos (as, in the spirit of full disclosure, once did I).

The deep love Father Hesburgh had for his God, his country and his beloved university spills forth on nearly every page.

But his vision -- the creation of, in his own words, "a great Catholic university, the greatest in the world!" -- wanes without a commitment to pursue both descriptors concurrently, and rests on the ability of his successors to live up to that mantra. Father Miscamble states that Father Hesburgh "did not succeed fully in his ambition," and rightly points out that the merit of that effort will be told in the fruit of its harvest. Its success remains an open question.

Father Miscamble's careful study reads Father Hesburgh's life as a signpost -- one that inspires many with the example of an American priest who influenced presidents from Eisenhower to Obama and served on innumerable committees and commissions, but also warns all that gaining such influence does not come without tradeoffs. "American Priest" asks readers to wonder what Father Hesburgh's influence would have been had he been more willing to be a signpost of contradiction as well.

- - -

Brown writes from Columbia, South Carolina.